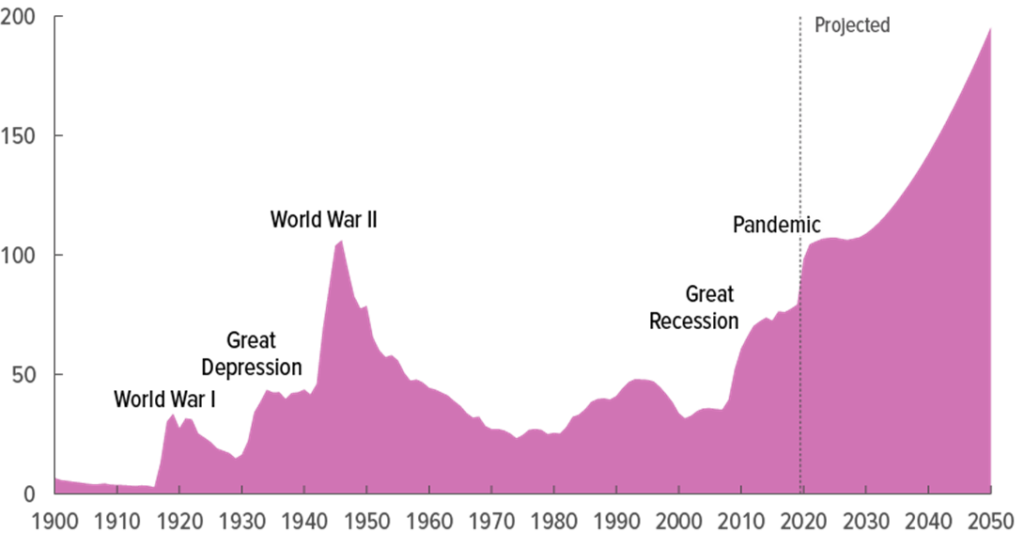

The tsunami of monetary and fiscal stimulus this year is a continuation of the policies implemented when the Financial Crisis began. When these first started the few who wondered aloud whether these policies were taking us down the same road as Japan were told to stop being ridiculous. Twelve years on and the parallels are stronger than ever. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand now owns 37% of the nation’s government bonds, up from 6% a mere seven months ago. The graph below from the Congressional Budget Office shows their projection of US government debt levels based on current taxation and spending levels. Many Western economies are not just following Japan, they seem intent on catching up in the zombie economy stakes.

Is Japan that bad?

It’s worth considering how Japan’s economy has performed for the last 30 years if for no reason other than to give modern monetary theory (MMT) proponents a quick history and economics lesson. Three measures provide a useful snapshot. The most positive is unemployment, where Japan has an enviable rate of just 3%. There’s cultural factors, a lack of migration and an ageing population pushing it down but this is undoubtedly a good number. A counter to this is GDP per capita, where the number now is the same as 1994 having zig zagged in the years in between. The population is employed but it is not being used productively.

Lastly is the government debt to GDP ratio with Japan being the world leader. Whilst there’s budget deficits every year, in good times Japan’s GDP grows a little so the ratio remains roughly steady. However, there’s a spike during every economic downturn as GDP falls back and the budget deficits blow out leading to an ever worsening position over the long term.

Putting all three together, Japan has thrown the proverbial kitchen sink of monetary and fiscal stimulus at its economic problems over the last 30 years and has nothing to show for it except an enormous debt load. Japan’s example should ring an alarm bell for anyone with a basic understanding of economics. It shows that the diagnosis was wrong and another course of action is needed.

Why are Western economies following the same playbook?

The best answer is that this is all about short term outcomes and politics. Politicians want to win the next election and should therefore be expected to choose short term stimulus over long term outcomes almost every time. Some argue that the current state of the media and the voting public has changed and that long term actions can no longer be implemented, especially when there’s pain for vocal special interest groups. I’m not convinced, there’s always been partisanship and yet previous generations dealt with economic downturns and wars far worse than ours has.

What has changed is the willingness to ignore long term consequences in policy making. It was previously understood that governments should run balanced budgets over the long term, but systemic budget deficits have been embraced by both sides of politics (and increasingly economists) since the onset of the Financial Crisis. Politicians and many economists naively argue that there’s a free lunch to be had from deficit spending and monetary easing.

Another change is the politicisation of the public service and institutions like central banks. Rather than needing to be seen as independent, treasury departments and central banks have become cheerleaders and apologists for short term stimulus measures. We no longer see balance in the arguments and advice in the public arena. Those who are hired and who stay employed in these roles understand that they must kowtow to the government actions of the day or they will be replaced by those who will. It looks like the economic equivalent of what the Chinese government has done to the parliament of Hong Kong.

For those who think this is excessive criticism here’s a few simple questions almost never discussed by policy makers:

- When will the stimulus measures be withdrawn and surpluses/normal interest rates return?

- Is there a time or level at which stimulus measures will stop (either by choice or by market forces) even if economic targets (inflation, unemployment) are not reached?

- Where is the evidence that low inflation or deflation is a problem?

- How will inflation be stopped if it gets out of hand?

- How will we deal with the risk that creditors will cease lending to governments that spend excessively?

- Why are policies that reduce long term economic growth being implemented?

- Why are policies that exacerbate systemic risk being implemented?

So what’s the endgame?

What’s clear from the above is that governments and central banks have embarked on a journey with no clear idea of where they are going and how they will get there. Every time a roadblock is reached there’s a further series of compromises made, without contemplating why so many roadblocks are being hit. Governments and central banks have no endgame, just an idea that they have to do something to get away from the current position.

There’s five different ways this could turn out. The optimistic outcome mirrors the decades after World War 2 when solid economic growth, population growth, productivity improvements and negative real rates combined to allow governments to “grow into” their debt levels. Whilst the starting position might look similar this outcome is unlikely as government are avoiding the policies needed for productivity improvements and demographics are more likely to be a headwind than a tailwind.

The second is the muddle through outcome, which looks like what has happened in Japan between economic downturns. Debt to GDP ratios are steady as budget deficits that increase debt levels are roughly offset by economic growth that increases the GDP line. The problem with this scenario is that it requires a cessation of economic downturns, a particularly unlikely scenario when current policy settings have substantially raised systemic risks.

The third outcome starts out like the second, but after a period of stable economic times an inevitable downturn arrives. This time though, monetary and fiscal policy are unable to respond and a depression occurs. Governments are forced to stand back and let decades of poor investments and short term policy decisions unwind in an overdue cleansing of excesses. The Asian Financial Crisis and Iceland’s depression after the Financial Crisis are examples. Whilst this is initially painful (think 5-10 years to get back to the previous GDP peak), these examples both show that after a deep cleansing, the economy is reset and ready to grow strongly once again.

The fourth outcome starts as a variation of the third but rather than conceding to a depression, policy makers go all out on stimulus measures. This look likes Weimar Germany of the 1920s as well as Argentina and Turkey today. Governments that adopt this option see their currencies collapse and ability to borrow cut off, whilst those that choose the third outcome don’t. If it really gets out of hand economic collapse akin to Venezuela or Zimbabwe can occur.

The fifth outcome starts out similar to the third, but instead of waiting for a downturn before taking action, policy makers recognise their errors and revert to orthodox monetary and fiscal settings. This will obviously have negative short term consequences as policies that pulled forward economic activity are unwound. Speculative activity and excessive debt levels will require restructures with equity holders zeroed and debts written down. Rather than continually hitting the stimulus button, policy makers now use the recession to push through long overdue productivity reforms. As a result, the period to get back to the previous GDP peak is reduced to 3-5 years with the next two decades of economic activity beginning with a firm foundation for solid economic growth. The rarely mentioned, short and sharp depression in the US in the early 1920’s is an example of this outcome.