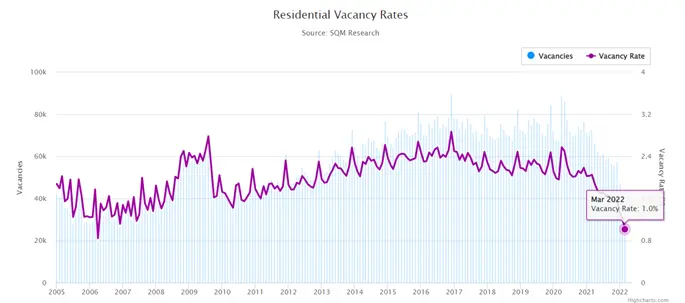

For many low and medium income Australians, the biggest issue in the upcoming Federal election is the cost of living. The quarterly CPI reading of 5.1% headline/3.7% underlying showed that the cost of goods and services is rising faster than it has in a long time. Petrol prices, groceries, housing and education all saw significant moves higher in the last quarter. Whilst some of these increases may level off in the medium term, rental affordability is set to get much worse. The chart below from SQM Research shows the plummeting national vacancy rate for residential property.

Data from Domain has Sydney and Melbourne above the average with Adelaide, Canberra, Hobart and Perth sitting well below 1.0%. Following the re-opening of international borders, foreign students and tourists have returned. There are widespread anecdotal reports of rental properties being withdrawn from the residential market to take advantage of higher yields from short stays. Even though the building industry is fully employed, completions have slowed due to issues with obtaining supplies and the insolvency of builders. After a short period of housing supply exceeding demand due to Covid impacts, a return to the undersupply position of the previous 15 years has now occurred.

Despite the lack of available housing and early indications of spiking rents, business groups and universities are calling for a surge in migration. The usual vague justifications about “being good for the economy” are made whilst the obvious consequences (where will these migrants live) are ignored. The brutal reality is that a surge in migration will result in a greater proportion of lower income Australians having to share properties amongst multiple families, or worse, living in caravans, cars and tents.

There are a range of solutions put forward, but they can all be captured under the truism that “there are no solutions only trade-offs”. Anglicare’s annual report on rental affordability does a very good job of analysing the data and making clear that there is limited affordable housing available for those on low incomes. Their proposed solutions are to increase government payments, build social housing and expand other government schemes for low cost housing, increase restrictions on rent increases and reform the tax system. Except for tax reform, which is a key part of long overdue productivity reforms, the other recommendations come with substantial costs and could result in less housing being available for rent in the long term.

The House of Representatives review of housing affordability did a good job of consulting widely and evaluating opposing arguments on how to respond. Their recommendations for reducing supply restrictions, cutting government charges and tax reform would increase the affordability and supply of housing if implemented. However, these are medium to long term changes that will do little to address the current imbalance.

At best, there are a handful of measures that could have meaningful impact in the short term, without negative long term consequences. First, carrot or stick measures could encourage the estimated 11% of housing that is unoccupied to be made available for immediate rental. Second, medium and long term migration can be slashed except for the most critical arrivals. Third, unemployed Australians who are available for work should be directed to accept vacancies in their local area, which would decrease the demand for imported labour and increase their income. There’s no magic solution to this problem created by governments over the last 15 years, but without action it will rapidly worsen.