When considering where the global credit cycle is at, it’s often easy to form a view based on a handful of recent articles, statistics and anecdotes. The most memorable of these tend to be either very positive or negative otherwise they wouldn’t be published or would be quickly forgotten. A better way to assess where the global credit cycle is at is to look for pockets of dodgy debt. If these pockets are few, credit is early in the cycle with good returns likely to lie ahead. If these pockets are numerous, that’s a clear indication that credit is late cycle. This article is a run through of sectors where I’m seeing lax credit standards and increasing risk levels, where the proverbial frog is well on the way to being boiled alive.

Global High Yield Debt

Last month I detailed how the US high yield debt market is larger and riskier than it was before the financial crisis. The same problematic characteristics, increasing leverage ratios and a high proportion of covenant lite debt, also apply to European and Asian high yield debt. Even in Australia, where lenders typically hold the whip hand over borrowers, covenants are slipping in leveraged loans. The nascent Australian high yield bond market includes quite a few turnaround stories where starting interest coverage ratios are close to or below 1.00.

Defined Benefit Plans and Entitlement Claims

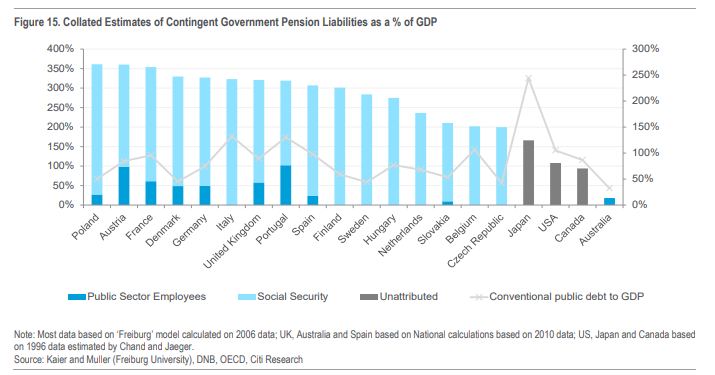

For many governments, deficits in defined benefit plans and entitlement claims exceed their explicit debt obligations. The chart below from the seminal Citi GPS report uses somewhat dated statistics, but makes it easy to see that the liabilities accrued for promises to citizens outweigh the explicit debt across almost all of Europe.

In the US, S&P 500 companies are close to $400 billion underfunded on their pension plans. This doesn’t seem enormous compared to their annual earnings of just under $1 trillion, but the deficits aren’t evenly spread with older companies such as GE, Lockheed Martin, Boeing and GM carrying disproportionate burdens.

Latest forecasts have US Medicare on track to be insolvent in 2026. At the State government level Illinois ($236 billon) and New Jersey ($232 billion) both have enormous liabilities, mostly pension and healthcare obligations. If you want to understand how pension and entitlement liabilities have grown so large, my 2017 article on the Dallas Police and Fire Pension fiasco and John Mauldin’s recent article “the Pension Train has no Seatbelts” are both worth your time.

US State and Municipal Debt

Meredith’s Whitney’s big call of 2010 that US state and local government debt would suffer a wave of defaults is generally considered a terrible prediction. However, after the 2013 default of Detroit and the 2016 default of Puerto Rico history might ultimately record her as simply being way too early. Illinois is leading the race to be the first default over $100 billion in this sector, but New Jersey and Kentucky could make a late surge. When the next crisis strikes and drags down asset prices, these states will see their pension deficits further blowout. At that point, there’s no guarantee they will continue to be able to rollover their existing debt.

The key lesson from Detroit’s bankruptcy was that bondholders rank third behind the provision of services and pensioners in the order of priority. Recovery rates of less than 30% should be expected when defaults occur. The key lesson from Puerto Rico was that just because a state or territory isn’t legally allowed to default, doesn’t mean that the Federal Government won’t intervene to allow creditors to suffer losses.

US Mortgage Debt

In the 2003-2007 housing boom, subprime residential lending was largely the domain of private lenders. Fast forward to today and the government guaranteed lenders are busy repeating many of the same mistakes. Borrowers with limited excess income and little or no savings are again getting loan applications approved. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac remain undercapitalised with their ownership status unresolved, leaving the US government to pick up the tab again when the next wave of mortgage defaults arrives.

Developed Market Housing

It’s not just the US with excessively risky housing debt, Canada, Australia, Hong Kong and the Scandinavian countries are all showing signs of some borrowers taking on too much debt. Canada deserves a special mention as it combines skyrocketing house prices with second lien, HELOCs and subprime debt. It’s hard not to make comparisons with the US, Ireland and Spain pre-crisis when you see those factors present.

US Subprime Auto

The occasional articles claiming that US subprime auto debt is this cycle’s version of subprime residential debt are substantially overstating the potential damage that could lie ahead. Cars cost an awful lot less than houses with auto securitisation volumes today running at around 7% of subprime home loan volumes in 2005 and 2006. This isn’t an iceberg big enough to sink the Titanic but it is a warning of the presence of other icebergs.

The quality of subprime auto loans is poor and getting worse with minimal checks on the borrower’s ability to afford the loan. Whilst unemployment has been falling, default rates have been increasing, a clear indication of how bad the underwriting has been. Lengthening loan terms and higher monthly payments are some of the ways lenders have been responding to the rate increases by the Federal Reserve. Some debt investors aren’t too worried though, recent deals have sold tranches down to a “B” rating. In 2017, issuance of “BB” rated tranches were sporadic but as margins on securitisation tranches have fallen investors have pushed further down the capital structure.

US Student Loans

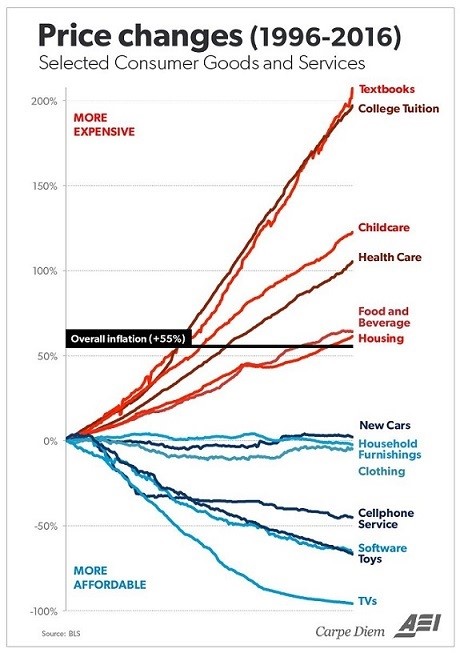

The chart below from the American Enterprise Institute breaks down US CPI into the various components. Textbooks and college tuition are the standout items with childcare and healthcare also notable. Soaring education costs have had to be paid by students, who ramped up their use of student loans. A handful of former students have managed to end up owing over $1 million. Total student debt owing is now $1.49 trillion up from $480 billion in 2006, more than credit card balances and auto loans.

Remember that many students never finish their degrees and others end up working in positions that don’t require degrees. This helps explain why over a quarter of student loans are in some form of default, deferment or forbearance. Most loans are owed to the US government, leaving taxpayers to foot the bill for defaults. Private lenders tend to cherry pick the better borrowers, often waiting until borrowers have graduated and found work before offering to refinance and consolidate their loans at a lower interest rate.

Emerging Market Debt

Whilst the developed market debt to GDP ratio has increased modestly in the last decade, emerging market debt levels have rapidly increased. China certainly skews these ratios with its extraordinary debt binge, but many other emerging markets have followed a similar pathway. The graph below from the IIF shows the combined ratios, but there’s a different make-up for developed and emerging markets. In developed markets the financial crisis led to soaring government debt to GDP ratios as governments ran deficits and bailed out banks and corporations. In emerging markets consumers, corporates, governments and banks have all increased their use of debt.

Debt markets are starting to wake-up to the risks with Argentina, Turkey, Mozambique and Bahrain all attracting the wrong sort of attention this year. This is a change from last year when I wrote about Argentina and Iraq selling bonds even though their prospects of repaying their debts appeared low. There’s been a long period of loose lending in much of the Middle East, South America and Africa similar to the conditions before the Asian financial crisis and the Latin American debt crisis.

Developed Market Sovereigns

The European debt crisis kicked off in 2009 with frequent flare ups since then. Greece’s default and restructure in 2012 saw private sector lenders take a haircut and contributed to Cyprus’s bailout later that year. The rolling series of ECB and IMF negotiations with Greece show that it’s structural problems are far from resolved and another default is likely in the long term.

Italy recently saw its cost of borrowing spike after the political parties that formed the new government considered asking the ECB for €250 billion of debt forgiveness. Both Greece and Italy have very high government debt to GDP ratios, consistently low or negative GDP growth and precarious banking sectors. Other developed nations most at risk are Japan and Portugal, ranked first and fifth respectively on their government debt to GDP ratios.

European Banks

The link between banks and sovereigns is critical to their solvency. Failing banks are often bailed out by governments, further increasing government debt levels. Failing governments often bring down their banks, as banks typically use government debt for liquidity purposes often treating it as a risk free asset. Europe has both problematic governments (Greece, Italy and Portugal) and problematic banks, mostly in Greece, Italy, Spain and Portugal. Deutsche Bank stands out for its size, high leverage and losses in each of the last three years. Given Deutsche Bank’s market capitalisation is little more than 1% of its asset base and it has shown an inability to generate a decent profit, a bail-in of senior debt and subordinated capital is arguably the only way to rectify its perilous situation.

Chinese Corporate Debt

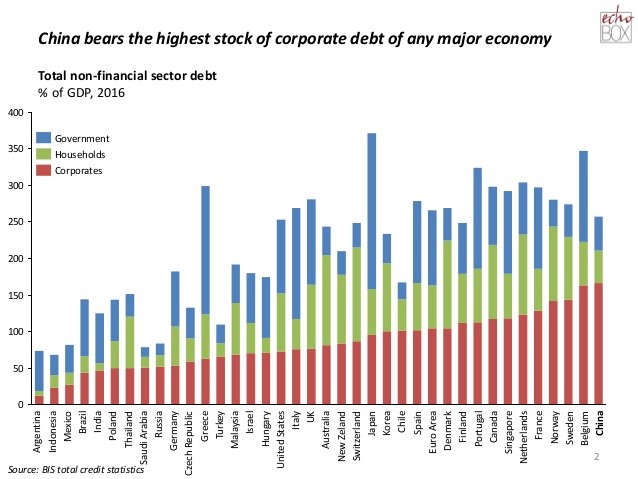

The rapid growth of debt in China since 2009 is dominated by the corporate sector. The chart below from Ian Mombru shows that China has the highest corporate debt to GDP ratio of any country. Close to half of the debt is owed by property companies and property linked industries. This is a major risk as Chinese property is overpriced relative to incomes and there’s widespread overbuilding, especially in the ghost cities. As with almost all debt in China, there’s several issues that make risk assessment far murkier than it should be.

First, many Chinese corporates have a material level of government involvement; by direct shareholding (state owned entities), shareholdings by high ranking communist party officials, direct and indirect government guarantees of debt, communist party representatives on committees or by having local or the national government as a major supplier or customer. The distinction between corporate debt and government debt, and whether government will support a corporate that gets into financial trouble is near impossible for outsiders to accurately assess.

Second, Chinese corporates often engage in guaranteeing or lending to other corporates. Guarantees range from non-binding letters of comfort to enforceable guarantees with the existence of these guarantees often undisclosed. The potential for one corporate default to trigger a wave of others is a known unknown.

Third, corporates have engaged in substantial margin lending of their own stock. One-third of A share companies have pledged more than 20% of their stock for loans, a substantial risk in itself. Yet this is made far worse when some of the companies pledging shares have little or no profit or are trading on P/E ratios above 100. The potential for a stock market crash to trigger widespread margin calls is a known known.

Chinese Banks and Shadow Banks

It’s often forgotten that China is still an emerging market in many characteristics, with the quality of credit assessment one of those. Credit assessment in China is often based on connections and the prospective return, rather than a thorough assessment of cash flows and collateral. Whilst the default rate has ticked up this year, it remains unusually low by international standards as weak borrowers are allowed to rollover their debts. Chinese banks continue to lend to marginal state owned entities and the shadow banking sector continues to support speculative private sector borrowers.

The bank and shadow bank sectors are linked in two key ways. First, banks often package, sell and guarantee shadow bank products, typically selling them to retail buyers as a higher return alternative to bank deposits. Second, banks provide leverage to shadow bank products in order to increase the product’s headline return. When China faces its first material test of lending standards since the 1990’s, the transmission mechanisms between banks and shadow banks will allow defaults to quickly spread. The prevalence of short term lending will also serve as an accelerant.

The Main Driver of Dodgy Debt

It’s frequently noted that recessions in the US typically occur after a series of Federal Reserve rate increases. The standard response is to assume that if rate increases were delayed or occurred at a slower pace then recessions could be avoided. This misguided thinking confuses cause and effect, ignoring the three ways that low interest rates encourage the build-up of dodgy debt;

(i) cheap debt allows a dollar of repayments to support a higher loan amount, allowing projects that wouldn’t normally proceed to receive the go ahead, inflating economic growth;

(ii) cheap debt causes a short term, temporary increase in investment returns (valuations increase in long dated bonds, equities, property and infrastructure) leading some to underestimate investment risks;

(iii) the above two factors combine to drag down prospective long term returns, leading to yield chasing as investors shift from safer assets to riskier assets to meet return targets.

This process is evidenced by last cycle’s credit and property bubbles in the US. After the 2002/3 recession began, the Federal Reserve reduced overnight rates to 1%, kick starting the cycle of yield chasing and malinvestment. By the time interest rates returned to neutral levels in 2006, speculative activity was widespread. Despite the obvious impacts of low interest rates in this and many previous cycles, central banks chose to set interest rates even lower and embark on quantitative easing in 2008. The alternative of a period of cleansing of excessive debt was deemed unpalatable. The inflated economic growth levels before the crisis were a benchmark that had to be exceeded. It’s no surprise the US, Europe and Japan have all experienced unusually slow recoveries from the last crisis as the necessary debt cleansing process has been avoided or protracted.

Conclusion

In reviewing global debt, twelve sectors standout for their lax credit standards and increasing risk levels. There’s excessive risk taking in developed and emerging debt, as well as in government, corporate, consumer and financial sector debt. This points to global credit being late cycle. Central banks have failed to learn the lessons from the last crisis. By seeking to avoid or lessen the necessary cleansing of malinvestment and excessive debt, this cycle’s economic recovery has been unusually slow. Ultra-low interest rates and quantitative easing have increased the risk of another financial crisis, the opposite of the financial stability target many central bankers have.

For global debt investors, the current conditions offer limited potential for gains beyond carry. With credit spreads in many sectors at close to their lowest in the last decade, there is greater potential for spreads to widen dramatically than there is for spreads to tighten substantially. Keeping credit duration low, staying senior in the capital structure and shifting up the rating spectrum will cost some carry. However, the cost of de-risking now is as low as it has been for a long time. If the risks in the dirty dozen sectors materialise in the medium term, the losses avoided by de-risking will be a multiple of the carry foregone.