The cyclicality of investor sentiment and asset classes has been a strong theme in recent months. The sell-off in high growth stocks and SPACs, rising bond yields and the jump in energy prices all involve a reversal of previous trends. Many investors struggle to stand back from a trend and consider history and future profitability when allocating capital. Running with the herd always seems to be the safest option in the short term.

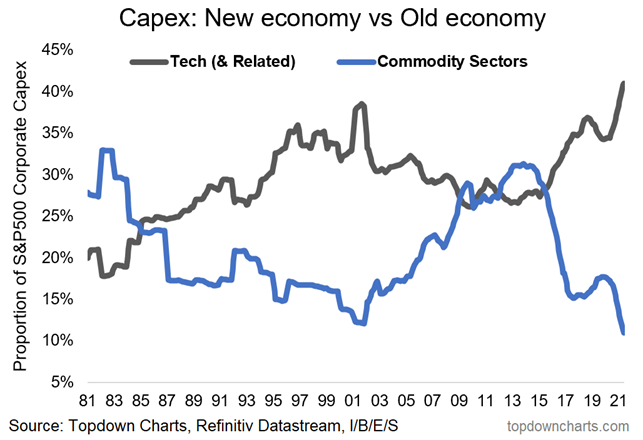

The chart below from Callum Thomas at Topdown Charts highlights the cyclicality in capital expenditures in technology and commodity sectors for S&P 500 stocks. Note the bump in tech investment in the late 90’s and early 2000’s and the subsequent bump for commodities in 2009-2015. These bumps align with the tech boom and the oil price boom respectively, an example of capital chasing historical returns.

Arguably the most major recent cyclical change is rising bond yields. After 30 years of seeing yields trend lower, we could be on the cusp of a substantial break higher. As inflation readings have consistently printed above expectations, markets have upped their expectation of where central banks will lift interest rates to. Most stark has been the jump in short term yields as central banks pivot from ignoring inflation to responding to it. However, long term yields have moved far less than they could have, still around 2% for 10 year government bonds in Australia and the US.

This disconnect was noted by Philip Lowe in a recent Q&A session. He observed that markets were essentially saying that US inflation could fallback from 7.5% to 2% without needing positive real interest rates, which is a rather heroic assumption. He then went on to say that he hoped to see positive long term real interest rates, as that has historically been associated with higher levels of economic growth and productivity.

This is something I have been writing about for years but it is the first time I can recall a central bank leader stating this obvious point. We should want higher interest rates because low rates promote speculative rather than productive activity, with an increase in productive activity the key to long term prosperity. (The other 2 P’s in the 3 P’s of economic growth, population and participation, are largely exhausted for Australia without incurring substantial costs.)

Market pricing says that the current batch of central bankers don’t have the nerve to increase rates significantly to address inflation. Whilst this is probably right, the possibility of long bond yields getting back above 4% has gone from remote to realistically foreseeable. Central banks have strayed so far from their targets that they risk political pressure being poured on them to act. If a politician is under pressure from voters because of elevated and widespread CPI, why wouldn’t they hold central bankers to account for failing to act? A small example is the change in tone from Jerome Powell and Lael Brainard after they were announced as the Fed Chair and Vice Chair late last year.

Turning back to the cyclicality of capital allocation, one additional point to remember is that for investment markets demand creates its own supply. (This might sound strange coming from a supply side economist.) If the last few years have taught us anything about high growth investments (or more cynically, investments that hold out a dismal prospect of generating lottery type returns) it is that markets will create something to satisfy the appetite.

If enough people want something that could theoretically be the next Google or Facebook, entrepreneurs will create a money losing meal delivery service or scooter rental business to sell to them. The same principle applies to SPACs with the strong early returns attracting a flood of capital that could overpay for money losing meal delivery services and scooter rental businesses. We now appear to have passed the turning point on these high risk endeavours with long shot companies and SPACs copping a pasting in recent months.