George Bush once famously mangled the old saying “fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me”. Whilst it’s embarrassing watching the video of him trying to get out the words, it’s going to be even more embarrassing for investors in the coming years when they realise they’ve been fooled twice. In both equity and debt markets investors are buying securities that have identical characteristics to the disasters of the recent past. Whether it’s initial public offerings (IPOs), tech shares, housing debt, high yield debt or sovereign debt, previous booms and busts give us a very clear guide of what will eventually end badly.

Tech Wreck 2.0

One of the most consistent ways to gauge the bullishness of equity investors is to assess the quality and quantity of IPOs. IPO volumes tend to rise through the cycle, peaking when equity indices are near their peaks. This makes sense as those who own and manage businesses are generally well placed to identify when the market will pay them a favourable price for their business. 2019 has so far been a boom year for IPOs in the US, with it likely to be one of the best years since the record volumes of 1999 and 2000. When private capital raisings are included the recent boom is even bigger, with venture capital investments in 2018 smashing the record from 2000.

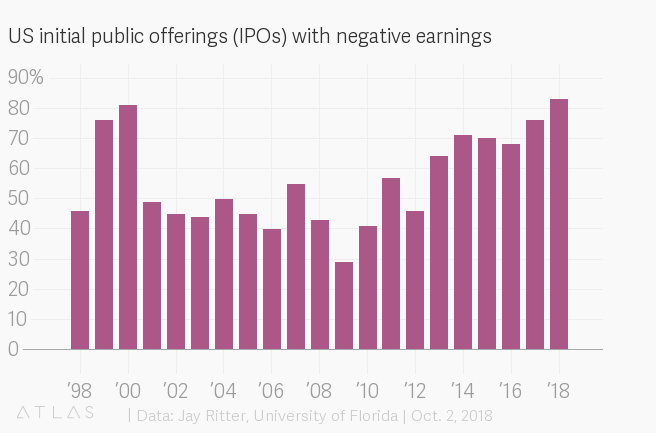

A good indicator of IPO quality is the percentage of new issues that are unprofitable. This topped 80% in 2000 at the height of the tech bubble, but this level was surpassed in 2018. Buying businesses that lose money indicates investors are preferring hope over experience.

The IPOs of Uber and Lyft this year have both been high profile doozies that sum up the mood. Lyft went first pricing at $72 per share and is now trading around $57. It’s larger competitor Uber priced at $45 per share and is now sitting below $41. Both companies have a long history of using capital raisings to cover their losses, with no plans to become profit-making companies any time soon. Roger Montgomery’s pre-IPO analysis of Uber is well worth a read, he likened it to a hot potato that its backers were desperate to palm off to others. Harris Kupperman shares the sentiment, he posited that Uber’s IPO was so big it might have soaked up most of the remaining speculative capital that punts on these sorts of ventures.

Two potential future IPOs that look like twins of Tech Wreck disasters are Chewy.com and WeWork. Chewy.com is an online pet supply company that lost $268 million in 2018 on $3.5 billion of sales. It looks an awful lot like pets.com, the poster child of the Tech Wreck which managed to go from IPO to bankruptcy in a mere 10 months in 2000. WeWork is an office sub-leasing business that lost $1.9 billion on $1.8 billion of revenue in 2018. It looks a lot like the Tech Wreck office space firm Regus, which filed for bankruptcy in 2003.

One of the hallmarks of the Tech Wreck was dodgy financial information and dubious measures of success. Technology companies are often pioneers, whether that be in the software and services they provide or in their ability to come up with distracting metrics. Some may remember the obsession with “eyeballs” rather than earnings back in the tech boom days. That sounds an awful lot like the monthly user counts that some investors are religiously monitoring today.

Some of today’s tech giants (notably Google and Facebook) have done a great job of turning their huge number of users into advertising revenue streams, leading some to assume that all companies with large user bases will inevitably be profitable. Forgotten in this assumption is the need to have a near monopoly on a service that competitors can’t easily replicate. The likelihood of Uber and Lyft turning out the same way as Google is extremely low as the proliferation of alternative taxi services shows that consumers can quickly shift to another service that offers a better deal. The inability to turn a profit when scale efficiencies are already substantial is another warning sign that shareholders are likely to be subsidising users for quite a while yet.

In order to offer a fig leaf of credibility to their current valuations, many tech companies are creating bizarre financial terms. My favourite is “community adjusted EBITDA” for WeWork, which excludes taxes, stock grants, marketing and administrative costs. Tesla has long been called out for accounting shenanigans with the regular turnover of its most senior accounting and financial officers another warning sign. Tesla’s attempts at disguising its high level of cash burn recently came unstuck. The announcement this month that it would run out of cash in ten months without radical change has seen its share price sink to almost half the level it was six months ago. It’s only taken 20 years but the hallmarks of excess in the Tech Wreck are back in play again.

Debt Wreck 2.0

The low point of the Financial Crisis was just over a decade ago, but lessons that should have been learnt have already been forgotten. The debacle that was US subprime mortgages has come back to life in a smaller way. The US mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have been busy cutting back on the down payments required and loosening restrictions on the minimum income a borrower needs to service a loan. Lending quality on FHA loans favoured by first time home buyers is particularly poor. This time around it will be US taxpayers picking up the tab through the government ownership and insurance of the mortgage aggregators. It’s not just the US where dubious mortgages are proliferating, Canada, Spain, several Northern Europe countries and Australia have all been called out for excessively easy housing credit.

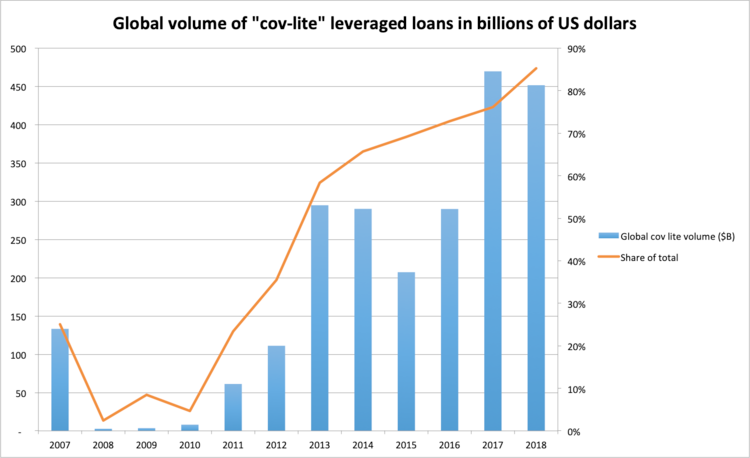

Global high yield debt markets seem determined to go beyond the stupidity seen in 2006 and 2007. The collapse in covenants, which function as an early warning sign for lenders, is a flashing red light that lenders are desperate to push money out the door on almost any terms. In the lead up to the Financial Crisis, covenant-lite leveraged loans were less than 30% of total leveraged loans. Borrowers that were given covenant-lite loans typically had B+ or higher ratings, having some level of inbuilt cushion. Today only the worst of the worst borrowers can’t obtain a covenant-lite loan. Holders of covenant-lite loans should expect a slew of their borrowers to slowly bleed to death, with the lack of covenants having cut-off their ability to take early action when the borrower still has some equity value.

It’s a similar story for sovereign debt as the European debt crisis is likely to re-emerge in the coming years. Italy’s economy is showing the same signs that Greece did before its ongoing debt crisis, but Italy is almost ten times bigger. The doom loop of bank failures leading to government failures and vice versa hasn’t been fixed increasing the risk of systemic and cascading failures. Deutsche Bank’s share price hitting record lows shows it remains an enormous risk, but there are dozens of small and medium size banks in Italy and Spain that have and will continue to call upon their governments for additional bailouts.

In the US, a wide swathe of state and municipal governments continue to run up their debts, as well as accruing pension and healthcare obligations. States such as Illinois can add population decline to their list of issues, which reinforces the downward cycle as the smaller remaining population needs to regularly increase taxes to cover the increasing interest and pension obligations. The defaults of Detroit (2013) and Puerto Rico (2016) show what lies ahead for bondholders. Heavy debt haircuts will be required to allow these jurisdictions to right their financial position.

Emerging and frontier markets are now showing signs of kicking off another cycle of defaults and restructurings. The last year has seen Argentina, Pakistan and Turkey go from having easy access to debt markets to now needing assistance to meet their upcoming debt maturities. A slew of frontier economies including Iraq and Tajikistan have used the loose lending of recent years to issue debt despite having obvious challenges in meeting future repayments.

Conclusion

It has often been said that those who do not remember the past are doomed to repeat it. The investment decisions made by some in recent years bear the hallmarks of the speculative investments made before the Tech Wreck and the Financial Crisis. With the recent pullback in several high-profile tech shares, bank shares and the surging yields for a handful of emerging market sovereigns we might be witnessing the beginning of a necessary and inevitable process of taking out the investment trash.