Preference shares, more commonly known as hybrids or listed notes in Australia, have become a staple in the investment diet for many retail investors and self-managed super funds. When economic times are good and companies are doing well preference shares can provide steady dividends that are usually 1-3% higher than term deposits along with some small capital gains. However, as the tip of an iceberg warns of the substantial danger below the surface, the structure of preference shares and their performance in the global financial crisis both point investors to the possibility that their portfolios can be shipwrecked by preference shares.

An Age Old Warning

Whilst this article mainly discusses the relatively recent experience of Australian investors with preference shares, the warnings on these securities date back to at least 1949 when Benjamin Graham wrote the first edition of his classic book The Intelligent Investor. Benjamin Graham is often referred to as “the father of value investing” and the mentor of Warren Buffet. Amongst many tributes Buffet gives to Graham he is quoted as saying that The Intelligent Investor is “by far the best book on investing ever written”. In the book Graham writes about the structure of preference shares:

“Really good preferred securities can and do exist, but they are good in spite of their investment form, which is an inherently bad one… the preferred holder lacks the both the legal claim of the bondholder and the profit possibilities of the common shareholder.”

He goes on to note the reasons why investors buy preference shares:

“Many investors buy securities of this kind because they need income and cannot get along with the meagre returns offered by top grade (investment grade) issuers. Experience clearly shows that it is unwise to buy a bond or preferred which lacks adequate safety merely because the yield is attractive.”

On when to buy preference shares, Graham argues:

“Experience teaches that the time to buy preferred stocks is when their price is unduly depressed by temporary adversity… in other words, they should be bought on bargain basis or not at all.”

Despite the age of the comments they are likely to be new to most Australian investors. To help put them into context a break-down of the key negative features of preference shares follows with Australian examples used to highlight those flaws.

Preference Shares don’t have Equity Control Rights

In Australia, if investors holding more than 5% of ordinary shares object to the current management or Board of a company they have a right to call for an extraordinary general meeting. The dissenting shareholder group can then propose to change the current directors with a view to new directors changing the overall direction of the company. Preference shareholders have no such rights even when their dividends stop, providing that dividends to ordinary equity have also ceased.

Preference Shares don’t have Covenant Protections like Loans or Bonds

When a company fails to pay interest on its bonds or loans without prior permission from the lenders, it has contractually defaulted. This effectively hands control of the future of the company over to its lenders, which may ultimately result in insolvency with the Board formally handing its powers over to external administrators. Preference shareholders have no such contractual rights when their dividends are not paid. Their payments are at the full discretion of the Board and are also non-cumulative, meaning that a missed payment is forever lost. Whilst having no dividends might be an acceptable outcome for holders of ordinary equity who can also participate in capital growth, preference shareholders typically invest for regular income and get little or no benefit from the increasing equity value of a company. Holders of ELDPA and PXUPA would be well aware of their lack of equity or debt control mechanisms, even though they haven’t received any dividends for many years.

Preference shares have no protections to stop the issuer from becoming excessively leveraged if earnings decline or if the company chooses to issue large amounts of senior ranking debt. Excessive gearing increases the risk that a company will switch off dividends to ordinary and preference shareholders for many years in order to reduce a substantial debt load. Lastly, but perhaps most importantly, the biggest missing covenant is the lack of a maturity date. The implications of this are expanded further in the next point.

Preference Shares are Extended in the Bad Times and Redeemed in the Good Times

Whilst the Australian experience with preference shares is much shorter than the US one that Graham wrote about, investors here have experienced the same negative outcomes stemming from not having a maturity date. Many investors discovered in the last decade that step-ups don’t guarantee redemption at their expected call date, with twelve widely held securities (AAZPB, BENHB, ELDPA, MBLHB, MXUPA, NABHA, NFNG, PXUPA, RHCPA, SBKHB, SVWPA & TPAPA) still outstanding today that have gone past their expected call dates. Loans and bonds at these companies matured during the financial crisis, with new debt issued at significantly higher margins. Preference shareholders however are still stuck with the pre-crisis margin and step-up levels.

The opposite side of giving the issuer control over the timing of redemption is now starting to become evident. AAZPB and TPAPA are likely to be redeemed in the second half of 2014. Another potential candidate for redemption is GMPPA, as Goodman is likely to be able to replace the preference shares with cheaper senior debt. GMPPA currently trades above $100 reflecting the relatively attractive returns in the eyes of the market. Current holders are at risk of seeing that premium disappear if the company chooses to redeem the security, with the price drop of HLNG and HLNGA following the announcement they would be redeemed an example of what can happen.

The key issue linking AAZPB, TPAPA and GMPPA is that investors who bought in pre-crisis would have much rather been redeemed during the financial crisis as replacement securities offered better value then. Investors receiving redemption now are faced with much higher reinvestment prices, with the small step-ups paid on these securities an inadequate return relative to what could have been received investing elsewhere.

Preference Shares Can be Converted to Equity at the Worst Times

Most ASX listed preference shares contain the right for the issuer to convert the preference shares to ordinary equity at specific times. This conversion option is most likely to be used when the company is in financial difficulty and when ordinary equity is least desirable. The case of WFLPA preference shares is worth noting. Holders were offered the opportunity to exchange into ordinary equity in 2009. Those who took the opportunity received equity worth 22.9% less than the issue price of the preference shares. In 2010 Willmott defaulted on its debts with the ordinary equity and preference shares both wiped out.

Bank preference shares are now issued with a standard clause that they will automatically convert to equity in the event the Common Equity Tier One capital ratio falls below 5.125%. If this point is reached, the bank will have recorded substantial losses on its loans and shareholders are likely to question whether the bank will continue to survive. The prospect of a large scale dilution of ordinary equity will put additional downward pressure on the equity price. It may fall further still if preference shareholders are compulsorily converted and many respond by selling their newly acquired equity as quickly as possible.

Recent vintage bank preference shares also contain a maximum conversion ratio limiting the number of ordinary shares that can be received in a conversion process. This means a preference shareholder can receive shares worth substantially less than the $100 issue price of preference shares (note that PCAPA has a $200 issue price) if their preference shares are converted to ordinary equity.

Preference Shares have Much Higher Drawdowns than Bonds

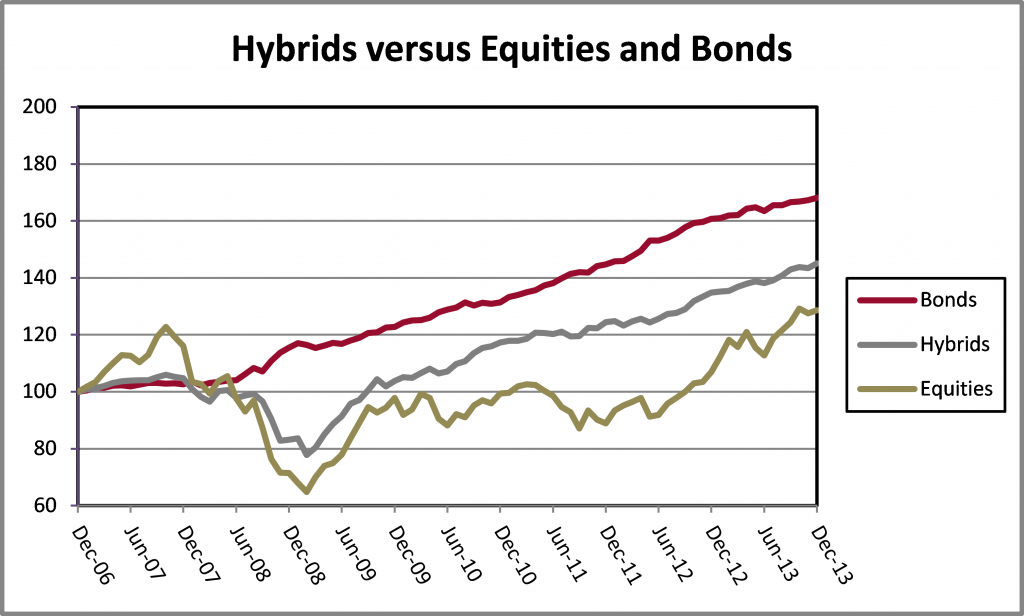

The experience of many Australian investors during the financial crisis aligns with the patterns of preference share trading identified by Benjamin Graham many years before. The graph below compares the ASX accumulation index, the Elstree Hybrid Index (an index that tracks a broad mix of ASX listed hybrids) and the S&P/ASX Corporate Bond Index using the data covering the seven year period from 2007 to 2013. This is an ‘apples with apples’ comparison as each index includes both capital and income return components. It shows a peak to trough fall of 47.2% for the equity index and 26.6% for the hybrid index, whilst the bond index fell by only 0.8%. The hybrid index did recover its losses much faster than the equity index taking 29 months compared to 71 months to return to the pre-crisis peaks, but bonds again proved to be far lower risk taking only 8 months.

The hybrid index may substantially understate the volatility many Australian investors actually experienced over the seven years. As an example, two publicly offered funds that specifically target Australian hybrid instruments suffered peak to trough falls of approximately 40%. Defaults with full loss of capital occurred on Allco (x3), Babcock and Brown, Great Southern (x2), Gunns, Timbercorp (x2) and Willmott. Holders of any of these securities would have learnt the hard way that hybrids often have limited upside like bonds, but the real possibility of a complete loss of capital like equities. Other negative outcomes include Babcock and Brown Infrastructure being restructured with a 57% capital loss and Elders and Paperlinx which both trade below 50% of the issue price and have not paid dividends for several years.

Conclusion

In the current times of low interest rates and low economic growth, many Australian investors are building their exposure to preference shares unaware of the risks they are taking. The lack of either debt covenants or equity control mechanisms leaves preference shareholders powerless to take action if their dividends stop. Preference shares also lack a maturity date. This means preference shareholders lose out as their capital is locked-up when other investment options are cheap, but given back when replacement securities are expensive. The timing of conversion to ordinary equity is also likely to be unfavourable, with substantial capital losses possible. In the financial crisis Australian hybrids showed that they should not be considered capital stable investments, with some funds suffering 40% peak to trough drawdowns, ten securities defaulting and suffering a complete loss of capital and another three suffering material capital impairment which has not been recovered.

Benjamin Graham warned of many of these issues as far back as 1949. Investors then and still today chase yield in bull markets, sacrificing protection measures like covenants in the process. Value investors following Graham’s advice will take advantage of the current low yields on Australian preference shares to sell down their positions and realise substantial capital gains. If Graham’s comments on the cyclicality of preference shares again prove to be true, then preference shares may once again be available at bargain basement prices.