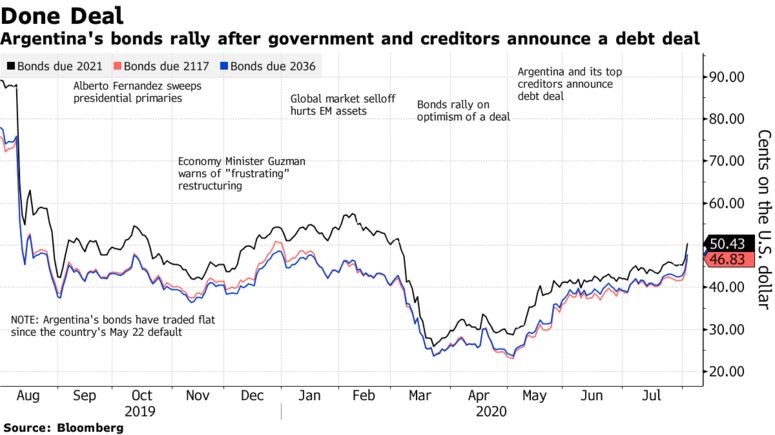

In June 2017 Argentina sold US$2.75 billion of 100 year bonds and I wrote then that “Argentina is unlikely to get through a decade without defaulting let alone 100 years”. It wasn’t a particularly radical call for a country that had defaulted four times in the previous 35 years. In August 2019 Argentina announced it planned to default and was seeking talks with its lenders to restructure its debts, sending the price of its bonds plummeting. This week Argentina struck a deal to restructure its debts on terms equivalent to 54.8% of the value of the old bonds. The obvious questions that follow are what does the deal entail and is anyone crazy enough to lend to Argentina in the future?

The deal agreed between Argentina and a majority of the bondholders owed $65 billion is still sketchy, with limited details released so far. It’s not clear what interest rate applies to the new debt, but principal repayments are almost all being pushed back beyond 2024. The credit rating agencies see this as a can-kicking exercise with substantial economic issues unresolved. There’s a decent chance that that holders of the new debt will get caught up in a future restructuring and have to take another round of haircuts. This scenario has already played out for some of those involved in Argentina’s previous debt restructurings, who are now copping a second reduction to their original investment.

Two main deal execution items are outstanding. First, a supermajority of bondholders needs to approve the restructure, which seems likely as a majority are already onboard. Given collective action clauses apply this time, it is unlikely that there will be a repeat of the holdout issues seen in the previous debt restructuring. Second, Argentina needs to reach agreement with the IMF, who it owes $44 billion. That will require economic plans to be agreed and implemented, which may involve unpopular cuts in government spending, taxation increases and an end to money printing.

Assuming a deal is finalised with both the bondholders and the IMF, ongoing payment of the new debt will come down to Argentina’s willingness to stick with sound economic policies. Based on Argentina’s deadbeat track record, economic reforms won’t last. Politicians inevitably find it easier to say no to international lenders who don’t vote than to the desires of their citizens who do. Added to that behavioural outlook is the current global economic downturn, which may mean Argentina has even less ability to pay in the future.

Whilst I’m pessimistic that Argentina will deliver long term economic reforms and make headway in repaying its debts, I’m not as downbeat on the possibility that the country will be able to attract new lenders. One precedent is Greece, which went from debt haircuts in 2012 to selling new bonds in 2014. Despite a sky high government debt to GDP ratio, a deadbeat track record and an aversion to necessary structural reforms, Greece’s 10 year bonds are currently selling at a mere 1% yield.

This sort of insanity can only exist in a world where central banks are punishing savers with negative or near-zero interest rates. If central banks reset overnight rates to a normal level of 4-5%, the increased interest bill would destroy the ability of overindebted sovereigns to service their debts. It’s funny that there are many studies highlighting the massive growth in zombie companies in the last decade, but zombie governments (e.g. Greece, Illinois, Italy, Japan) are mostly ignored. The default of these jurisdictions seems inevitable, but there’s a good chance another generation of lenders will be sucked into these yield traps before they default.