Argentina and Lebanon are Broke, so let’s Lend to Angola

The travails of Argentina are well known, they’ve defaulted on their debt yet again with bondholders now fretting over how big a haircut the country will try to impose on them. Less well known is Lebanon, its government debt to GDP ratio of 152% sees it rank behind only Japan and Greece on that measure. That ratio alone has had the country on the watchlist of lenders for a long time, but this year things have deteriorated for the nation of 6.1 million people. A slowdown in remittances from citizens living abroad, the wave of refugees from Syria and the hangover from a debt binge have combined to place the country in an almost impossible financial position.

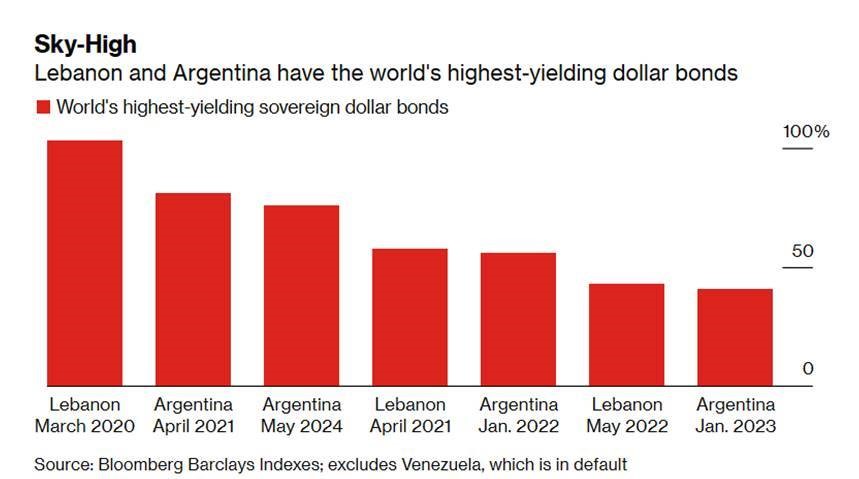

As reserves dwindled a bank run started with the government forcing banks to close for two weeks in order to stem withdrawals. Once banks reopened citizens turned up demanding full withdrawals, some armed with guns and unwilling to take no for an answer. Not surprisingly, demand has dried up to buy Lebanon’s bonds, pushing yields up to levels in line with Argentina, as the graph below from Bloomberg shows. Whilst Lebanon hasn’t yet defaulted, it is almost certain to do so in the near term.

You can add Ecuador to the list of problematic emerging market borrowers, its bond yields have also spiked after citizens and parliamentarians revolted against austerity measures required as part of its February 2019 IMF bailout.

Despite the issues with Argentina, Ecuador and Lebanon, Angola was able to attract $8 billion of orders for 10 and 30 year bonds this month. It ended up selling $3 billion of bonds, paying 8% on the 10 year bonds and 9.125% on the 30 year bonds. Angola is another IMF bailout recipient, and like Ecuador it has a heavy reliance on oil exports.

S&P has it at B-/negative outlook and Moody’s at B3/stable outlook. That rating puts it in true junk bond territory; borrowers who S&P refers to as the “weakest links”. Angola is seen by optimists as a turnaround story with solid growth potential. Time will tell whether bond buyers have fallen for the same old snake oil or if this time really is different for another weak emerging market borrower.

US Subprime is Back – this Time its Auto Loans

It’s no great secret that global automakers are having a tough time, sales are falling leading to inventory building and furloughs or shutdowns of production facilities. In Australia car sales have fallen 8% this year, with weak consumer sentiment and tighter lending standards post the Royal Commission taking the blame. China’s auto sales have seen a similar drop, whilst the US is just slightly negative. Getting finance in the US isn’t currently an issue, if anything it is far too easy to get a loan to buy a car. 86% of new car sales in the US are financed so changes in the availability of finance will have a substantial impact on the volume of future car sales.

In US auto lending, borrowers are graded into two main loan categories, prime and subprime. There’s some shading between those two categories, but as a guide subprime borrowers will pay an average interest rate around three times higher than prime borrowers. For the prime segment, arrears are very low as would be expected when unemployment is low.

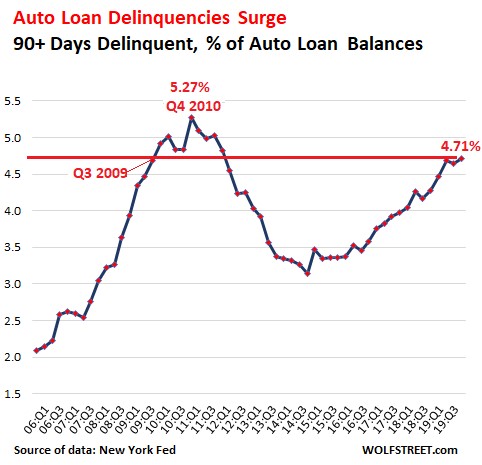

For subprime loans it is another story altogether with the graph below from Wolfstreet.com showing that arrears for all loans are now as bad as they were during the financial crisis when unemployment was far higher. As prime loans make up 78% of all loans and with arrears less than 0.5%, it’s a surge in subprime arrears that is driving the average US arrears rate higher. Over 20% of US subprime auto loans are in arrears, when unemployment is close to all time lows. There’s only one explanation for that, subprime lending quality is abysmal.

A recent article from Mish Shedlock highlighted a few crazy stories, including one borrower who took out a $45,000 loan for a $27,000 car. The $18,000 gap comes from the negative equity position on the old loan that the new lender is funding. In recent years around one-third of all auto loans have involved borrowers rolling over negative equity from one loan to the next. Another trend has been to amortise loans over a longer period, making the repayments smaller so the borrower can afford a larger loan. That then feeds back into the negative equity problem as the car is worth less than what is owed for a far longer period.

If you are getting those feelings of déjà vu all over again, that’s because this looks a lot like US subprime home lending from 2004-2007. Just as almost anyone could get a home loan then, now almost any American can get an auto loan. There is one big difference though, outstanding US auto loans total $1.3 trillion, a small fraction of the $15.6 trillion of US mortgage debt outstanding. Whilst this sector won’t cause a financial crisis on its own, it’s just another sign of the bad behaviour encouraged by central banks printing money and setting interest rates far too low.

Virgin Australia’s Very Junky Debt Raising

Virgin Australia is spending $700 million to buy back the 35% share of the Velocity frequent flyer program that it sold in 2014 for $336 million. It is funding the purchase through the issuance of A$325 million of ASX listed notes paying 8% interest and US$425 million of high yield bonds.

At a basic review the Virgin business is not unlike Tesla; some prospects of making a decent profit but the debt is being sold mainly on the equity story rather than credit fundamentals. A couple of basic financial points:

- The business has net assets of $619 million of which $581 million is intangibles. For a $6.5 billion balance sheet that’s effectively zero tangible equity.

- Current liabilities are roughly 1.5 times greater than current assets.

- Over the last 3 years the smallest loss was $186 million.

- Much of the fleet is security for other debts. There’s little in the way of hard assets for unsecured lenders.

- The market capitalisation of $1.3 billion is very small relative to the $6.5 billion balance sheet. For Qantas it is $10.5 billion versus $19.4 billion. This means even Virgin’s shareholders have doubts this business can generate a decent profit.

For me, a business like this is clearly in the CCC band. If there’s no profit, the debt to earnings and earnings to interest ratios are negative, but Moody’s has it at B2 and Standard and Poor’s at B+. These ratings would typically align with a business that can cover its interest from EBIT (earnings before interest and tax) 1.3-2.0 times. Yet Virgin has had negative EBIT for each of the last 7 years with no ability to cover its interest from earnings. The ratings are well ahead of the business, banking much of the hoped for turnaround benefits that the new CEO is promising. Given this business has a long history of under-delivering on turnaround strategies that’s a significant stretch.

The debt is also unsecured, which means it ranks behind the secured debt most notably aircraft financing. This is where the smart lenders play in the airline sector, making sure they have something valuable to grab when an airline can’t pay its debts. There are guarantees from and debt restrictions on some group entities, but importantly not from the Velocity business which generates a profit. This leaves open the possibility of Virgin adding more debt to this business if it can’t obtain anymore unsecured debt or debt secured against its aircraft, further subordinating the position of unsecured debt holders.

The major positive for unsecured debt holders is that shareholders have a history of tipping in more money, hoping that Virgin’s place in a duopoly will eventually yield profits. Whether that continues to hold true, particularly if there is a global downturn that makes the primary businesses of the major shareholders unprofitable for a time, is doubtful. At some point all rational investors stop throwing good money after bad, just as one of Virgin’s major shareholders did with Air Berlin in 2017 and Air New Zealand did with Ansett in 2001. Both of these situations resulted in the underperforming airlines going bankrupt and being dismantled.

Notwithstanding all the above, the debt raising was a smashing success more than doubling the A$150 million target with the bookbuild closing early. If you are looking for a case study of how low interest rates lead to yield chasing this is a pretty good one.