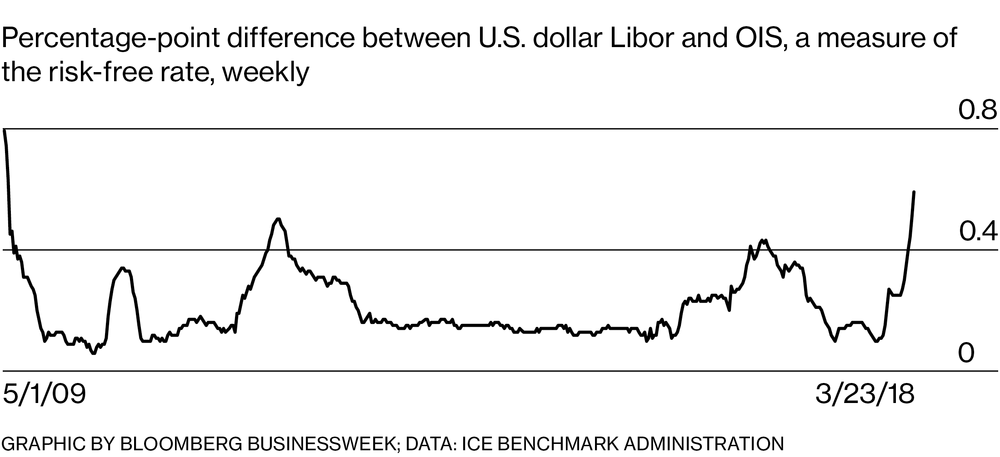

Libor Spike

The increasing gap between US dollar Libor and overnight index swaps (OIS) this year is garnering much attention as it was one of the earliest signs of problems in 2007. Libor is a compilation of the interest rates that major global banks charge when lending to their peers. The OIS is the market view of the anticipated cumulative overnight lending rate, typically at or close to the local central bank’s rate. There’s typically a higher interest rate for Libor than OIS, as the central bank is considered a lower risk than lending to a bank. As shown in the Bloomberg chart below, the gap between the two rates for a three month maturity has spiked to the highest level since 2009.

Three major reasons have been put forward for this jump. First, the US Treasury has conducted larger than usual issuance at the short end to fund the tax cuts and as a catch up for non-issuance during the recent budget stand-off. Second, corporates that were holding excess cash in money markets outside of the US are repatriating those funds to the US. The lower tax rate has enticed them to onshore the funds and spend it on buybacks, capital investments, higher wages and paying down debt. Third, the world is moving from quantitative easing to quantitative tightening, reducing the excess cash in markets.

The key question is whether the jump in rates is indicative of wider problems. In July 2007 the jump in the spread between Libor and OIS was one of several signs that a credit crunch was coming. The other major signs were a spike in credit default swaps (CDS) and the evaporation of liquidity for esoteric securities like CDOs and subprime MBS. There has been a small spike in CDS this month, but that is mostly from the semi-annual rollover of the index. Where there is limited liquidity in markets (e.g. Japanese government bonds) it is typically due to asset owners hoarding, fearing they won’t be able to replace securities if they sell. At this stage it’s a case of “be alert but not alarmed”.

Toy’s R Us Liquidation

Toy’s R Us (Toys) wasn’t able to find a buyer for all of its operations during bankruptcy and has transitioned to liquidation. This offers potential purchasers the opportunity to pick-off the profitable locations and leave behind the poorly performing ones. Sales have slumped in the last six months as suppliers pulled back and management was distracted fighting with creditors. The process that Toys is going through is a reminder of several key lessons when dealing with distressed companies.

First, the poor sales are being blamed on difficulties getting stock as suppliers were concerned about Toys ability to pay them. For many businesses and particularly retail, nervous creditors are the death knell. If you don’t have good products customers will go elsewhere. Businesses in financial distress must quickly rectify their capital position or the financial distress will create operational distress. I think of financial distress like the death zone when climbing Mount Everest; get the job done and get out quickly, as if you loiter you’ll die.

Second, it’s often a tough call whether a solvent debt for equity swap or a financial restructuring during bankruptcy is a better outcome for creditors. Toys tried but failed to convince creditors to swap their debt for equity whilst it was solvent. The creditors thought they would get a better outcome by a deeper financial and operational restructuring, which required a bankruptcy to execute. Bankruptcy has risks (keeping customers and suppliers) but it provides leverage in cutting away poorly performing locations and business units. At this stage, a debt for equity swap a year ago is looking like it would have delivered a better outcome.

Third, starting leverage and covenants matter. Toys’ leveraged buyout in 2005 left the company highly indebted. Without rapid growth, the debt was always going to be a heavy burden leaving it little excess cash to reinvest in store fit-outs, marketing and new locations. If the starting leverage had been lower, the company might have been able to grow into the debt by increasing earnings or amortising the debt. If there had been decent covenants these would have tripped long ago allowing creditors to press the private equity owners for more equity to rectify the capital structure. The combination of high leverage and low covenants is now common in global debt markets and points to a long and ugly default cycle in the next global downturn.

Potential Australian Franking Credit Changes

The Australian Labor Party has proposed changes to franking credits that it is estimating will deliver an extra $5 billion per year to the national budget. I’ll leave the politics of winners and losers to others but will pick up on two key economic points for this proposed change.

The first point is that broad based tax reform will deliver substantial economic benefits to Australians, including more jobs and investment. The blueprint for this can be lifted from the Henry review and the tax white paper process. It involves lowering income taxes, offset by higher and broader land tax and GST. Tinkering with franking credits, mining taxes or superannuation is relatively meaningless.

The second point is to remember that people respond to incentives. The combination of low interest rates and the full refunding of franking credits incentivised retirees to target high dividend stocks and bank preference shares. Whilst there’s no material change to the Australian cash rate on the horizon, changing the incentives around franking credits will result in investors changing their investment structures and portfolios. There’s already been plenty of loopholes identified where an investment structure change will nullify the proposed franking credit changes.

Investors that shift their portfolios away from high yielding stocks and bank preference shares to REITs, debt investments and growth stocks will also negate the changes. Whilst the budget savings are touted at around $5 billion per year, I’d be surprised if the outcome will be more than $2 billion per year after investors reposition. But that won’t stop the politicians from claiming they have $5 billion a year more of our money to “give away” at the next election.

Australian Banking Royal Commission

The Banking Royal Commission has kicked off with a flourish of surgical strikes against the major banks. Two main areas have been targeted thus far; the selling of inappropriate products and responsible lending compliance. Based on what has been seen thus far, the next twelve months will be brutal for the major banks as their misdeeds are publicly scrutinised.

The Commission has targeted the selling of inappropriate products such as advising a customer to switch from a lucrative defined benefit scheme to a far less lucrative superannuation scheme and pressuring customers to buy worthless insurance. The Future of Financial Advice legislation places an onus on advisers to act in a client’s best interest. There are some murky areas around when the best interest duty applies and what exactly is a client’s best interest. The Commission is highlighting the most egregious cases as it goes along, with the final recommendations likely to provide greater clarity.

What is clearer is responsible lending requirements. Lenders must (1) gather information, (2) verify the information and (3) conclude that the loan is not unsuitable. The Commission has torn the banks to shreds for systemic failures to verify the information gathered. It is well known that there is some level of lying on loan applications, a UBS survey found 33% of borrowers admitted to some degree of dishonesty. Evidence at the Commission has the banks admitting they think it would be too costly and time consuming to undertake reasonable checks. The flood gates are now open for consumers to sue if they lose money on property investments and for the regulators to issue fines.

The banks have attempted to shift the blame onto mortgage brokers, claiming that brokers are responsible for the documentation they provide. This is merely blame shifting and the Commission is likely to see through it. Brokers aren’t the lender and thus the bank must check the information they receive to comply. Both brokers and bankers have been caught coaching borrowers to submit false information to get dodgy loans approved. As well as trying to avoid responsibility, the major banks are using this argument to have broker commissions regulated and reduced, thus increasing their profits.

Lastly, APRA and ASIC have been shown to be asleep at the wheel yet again. None of the issues exposed have been a surprise to those familiar with the misconduct in the financial services. Whilst the Commission hasn’t heard their testimony as yet, it should be called upon eventually. Questions need to be asked of the regulators about how misconduct was able to continue for so long and why there hasn’t been any material penalties imposed other than reimbursing consumers. If this widespread misconduct happened in the US or the UK fines in the billions of dollars would have been issued long ago.