The World Bank Warns on Soaring Global Debt Levels

The December release of the “Global Waves of Debt: Causes and Consequences” report by the World Bank mostly slipped under the radar as people were focussed on Christmas celebrations and holidays. This is somewhat unfortunate as this report is one of those occasional, well researched pieces that reminds investors of the weak foundations of the global economic recovery of the last decade. To escape the ravages of the debt fuelled financial crisis of 2007-2009, we’ve gone on another debt bender. The World Bank is politely pointing this out and putting forward a few suggestions for governments to potentially lessen the risk of this renewed debt binge.

The report compares the current and largest debt wave to three historical examples; the Latin American debt crisis, the Asian financial crisis/tech wreck and the global financial crisis. The report details differences and similarities between the four waves, but most importantly notes that the latest debt wave is larger, faster and broader than the previous three. The report particularly points to growing debt levels in emerging markets but developed markets have also seen substantial growth in debt levels, particularly sovereign debt.

Arguably the World Bank report is too polite in two respects. First, developed economies mostly escape criticism with much of report focussed on emerging markets. This is understandable as the authors probably don’t want to do much more than nibble on the hand that feeds them. (The largest developed economies mostly pay the World Bank’s bills). Take the United States; despite very low unemployment and reasonable economic growth, deficits and sovereign debt growth are the order of the day. If now isn’t the time for sovereign deleveraging in America, there isn’t likely to be a point in the economic cycle where it would happen.

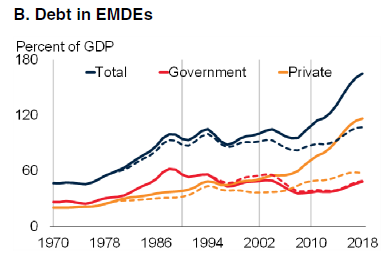

The second level of overly polite reporting is regarding China. The report does mention China’s debt growth, but more often it talks of emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs). When it comes to emerging market debt levels, growth in debt is almost all about China. The graph below from part 1 of the report illustrates this, the solid lines are the aggregate of all emerging markets and the dashed lines are all excluding China. Once the Chinese debt binge is removed, emerging markets in aggregate have seen little change in total debt levels.

The report also tiptoes around the growing problem of debt China has supplied to emerging economies. China has been aggressive in its lending to less wealthy nations, often for projects of dubious value. When the debt servicing inevitably becomes problematic, China has in cases been using the situation to gain control over key infrastructure or resources. Where previously there would have been a debt restructure with creditors simply taking a loss, China is using debt restructurings to gain control over key aspects of a country’s economy.

The report tries to end on an optimistic note, arguing that this latest debt wave can be managed through transparency, policy frameworks, regulation/supervision and corporate governance. History points to an economic hangover being a far more likely outcome from this debt bender.

For investors, the primary takeaway is a reminder that Chinese debt growth is unprecedented. Whilst Chinese debt is mostly internal and denominated in the home currency (emerging market debt busts often involve substantial foreign currency debts), this simply shifts the likely outworking of a debt bust. Rather than looking to Argentina or Venezuela as recent precedents, China looks much more like Japan in the late 1980s. It’s not just the debt growth and “miracle” economic growth that seems similar, the cultural and demographic likenesses are uncanny. A potential Chinese bust is therefore more likely to be a multi-decade malaise rather than a rapid plunge.

However, this scenario assumes that the heavy hand of the Communist Party remains. If an economic downturn leads to widespread revolt and a change of government, then a rapid plunge is the most likely outcome. This is one key difference with Japan, Chinese citizens have an unwritten bargain with their government that their continued submission relies upon their wealth increasing. If the wealth accumulation of recent decades turns out to be a Ponzi scheme, the citizens will turn on their government and there will be a fight for control. The current demonstrations in Hong Kong might be just a prelude to the main event.

Anecdotes of Yield Chasing

There’s a common question being asked of economists, money managers and financial commentators these days; are we mid-cycle or late-cycle? The honest answer is that we don’t know and we can’t know until the cycle has seen a severe downturn. We can clearly look back and say that the yields available on almost all asset classes are far less than they were five years. Yet we can’t predict the future; and we could see further yield compression from here or a long period of no change. However, in the spirit of having a view here’s a few anecdotes that point to the credit cycle being much closer to the end than the middle.

This week an Austrian bank sold €500m of preference shares (aka hybrids or CoCos) at a 3.375% dividend rate but had bids for 10 times as much as it sold. This is the second lowest yield ever printed for this type of security. The yields on European subordinated capital securities have fallen markedly over the last year with investors increasingly dismissing the structural and solvency risks that come with these securities.

Whilst bank hybrids have been a yield chasing tool of choice for Australia retail investors, the flavour of the month overseas is structured products. Investors in the US, China, India and South Korea have been punting on investments that offer the prospect of additional yield by selling options linked to currencies, equity prices or volatility. These trades tend to work well when markets are relatively calm, but burn investors when volatility picks up and asset prices fall.

The massive growth in private debt in the last decade has been well chronicled. This is partly a structural phenomenon as banks have reduced their remit and left more room for other lenders. There’s also been recognition that when done well, this sector delivers returns higher than vanilla equities with far less volatility. The current outlook for private debt could be summed up with the adage that “what the wise man does in the beginning, the fool does in the end”.

As the flood of money entered the sector in the last few years, yields have fallen and risks have increased. The increased risk can be seen in the reduction of covenants, the proliferation of earnings add-backs and the expansion in leverage multiples. Some lenders have responded by pushing into less competitive territory, often looking to lend to smaller and younger businesses. For some lenders, borrowers that don’t generate a profit and in some cases don’t even have any revenue are still considered bankable.

One more type of anecdote that often makes an appearance at the late stage of the cycle is the “this time is different” variety. Hedge fund behemoth Bridgewater is well known for its view of how the economy works and the drivers behind business cycles. This week its co-CIO made the comment that “we’ve probably seen the end of the boom-bust cycle”. This closely followed a remark from Bridgewater’s founder that “cash is trash”. This is an interesting turnaround in sentiment from a firm has badly underperformed the S&P 500 since 2012 due to its conservative risk positioning.

Three Overlooked Points on the LIC/LIT Fee Battle

The articles have been flying back and forth over whether financial advisors can accept commissions for selling LICs/LITs to their clients. If you haven’t been following this so far, Graham Hand wrote a well-rounded article recently, with Jonathan Shapiro and Christopher Joye also leading the charge. I’m not going to rehash the main points here but want to bring three additional points to the discussion.

Financial Advisors Shouldn’t Be Keeping Any Commissions

Whilst some are arguing that LIC/LIT commissions must go, they are supporting the continuance of commissions for other listed product types. There’s no decent argument for this, if a commission is viewed as biasing an advisor’s decision, they must pass the commission to their client or refuse it outright. Saying that an advisor has a conflict if the commission relates to a LIC/LIT but doesn’t if it relates to a hybrid or equity investment is non-sensical.

For those struggling with the concept of selling hybrids or equities on their merits and without an advisor commission, look to the institutional debt markets. These have long functioned without the need for commissions. If the bond is considered poor value it receives little interest, but if it is good value it is many times oversubscribed. There’s no reason that hybrids and equities can’t be distributed in the same fashion.

Brokers Can Keep Commissions, Subject to Disclosure

Those dealing with clients need to choose whether they are salespeople (brokers) or financial advisors. Whilst a financial advisor needs to adopt a best interest/fiduciary duty position and consider the wider client position, I don’t see that a broker should be subject to the same restrictions. A broker should however, be clearly disclosing that they are broker and are being paid for the sales they make. This could be as simple as a verbal statement such as;

“I am a salesperson not a financial advisor which means that I earn commissions by selling products and services to you. The products and services I am selling may not be in your best interest and you may want to seek independent financial advice before agreeing to purchase.”

Some might argue that this is overkill and retail investors are smart enough to know who is a broker and who is an independent advisor. I think the Royal Commission showed that not only were clients confused about the distinction but many so called “advisors” were as well.

LICs/LITs are an Appropriate Structure for Illiquid Investments

Some of the arguments against LICs/LITs seem to come from a viewpoint that open-ended managed funds are the best solution for retail investors as they always offer a quick exit at close to the net tangible asset calculation. This is fair for the most liquid sectors such as large cap equities or vanilla investment grade bonds. However, for more illiquid assets such as sub-investment grade debt, private equity, some hedge funds and direct property, history is littered with examples of funds that ran out of cash and locked their investors in. If the assets take substantially longer to sell than the redemption period on the fund, investors and managers are playing with fire.

Given this, unlisted closed ended funds (e.g. direct property syndicates, private equity funds), individual mandates or LICs/LITs are the most appropriate vehicles for illiquid assets. As many retail investors insist on having some form of liquidity, a listed fund is likely to be their best avenue to access these sectors.

Critics of listed funds often point to the higher fees (from listing and governance costs) for these funds compared to their unlisted equivalents. This isn’t always true, with fees running at over 1% per annum for retail investors on some open-ended unlisted funds. It also ignores that higher fees could be more than offset by higher returns as listed funds do not have to hold large cash positions to offset the run on the fund risk that open-ended unlisted funds come with.