Covenant Lite

You know it’s late in the credit cycle when credit investors give away their key protections in return for just a little more yield. This acquiesce comes in different forms, including higher levels of leverage, longer dated debt, subordinated debt and weakened or eliminated covenants commonly referred to as “covenant lite”. This risk creep happens every cycle. It always looks stupid after the cycle turns and the weaker securities suffer the biggest losses. Yet if it’s so obviously wrong why do credit investors keep doing this?

The small yield pick-up is part of it but not everyone is solely focussed on the short term. It could be new entrants to the markets, as half of fund managers weren’t around in 2008. But even then, the old managers who have been around for long enough often get caught up in it.

The analogy of boiling the frog is also part of the answer. If a credit manager in 2010 was asked to take on the substantial risk for minimal returns offered today they’d say no immediately as conditions then were so different. Over time though, the heat has turned up and they’ve gradually lost the margins and the protections they had in 2010.

Another factor is that people find ways to justify why it isn’t that bad. One recent article noted that covenant lite critics are often rating agencies, academics and commentators rather than lenders. They argued that lenders prefer covenant lite as dealing with covenant breaches is a big drain on resources. It sounds good, until you realise that dealing with defaults (including explaining the losses to your investors) is a far bigger drain on resources!

This sort of errant justification isn’t limited to credit. A common error in equities is to compare the current forward P/E ratio with historical P/E ratios. There’s also the arguments about whether to use adjusted earnings or accounting earnings; the former makes everything look much better. The current Schiller P/E ratio also looks better if you remove the impact of the financial crisis, ignoring that a ten year lookback period almost always includes a recession. Property and infrastructure investments look much better if you assume interest rates will never return to levels that we used to consider normal. Now is a great time to take a step back and reflect on why we buy what we buy.

High Yield Defaults

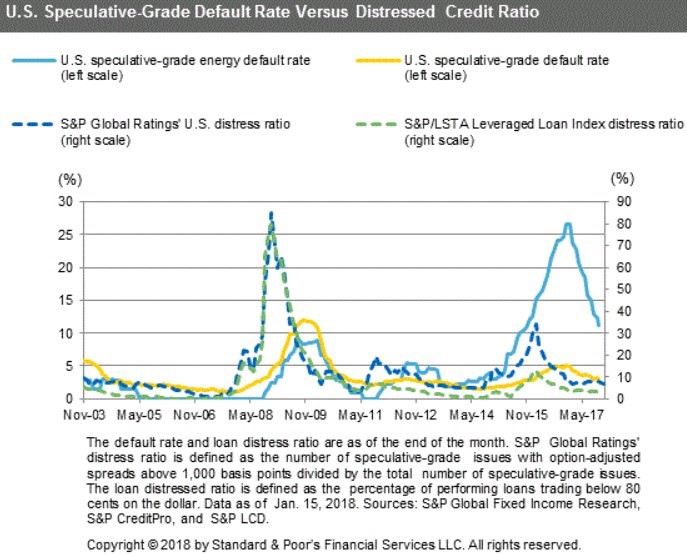

Similar to the misunderstandings with covenant lite is the use of high yield default rates to predict future high yield returns and the probability of a US recession. It may have been a leading indicator in the past, but with covenant lite lending now at 76% of outstanding loans it is likely to be a lagging indicator in the future. What will work better is the distress ratio, which is the proportion of securities that have a yield greater than US treasuries + 10%.

The distress ratio is an early stage sign that credit investors are losing faith in the ability of sub-investment grade borrowers to refinance their debt or raise additional equity to deleverage. When a security margin trades above treasuries + 10% credit investors are pricing in a substantial probability of default. Keep in mind that the main high yield bond index is currently trading at treasuries + 3.41%, so the distress ratio today captures securities that are well away from the average. As shown in the Standard and Poor’s graphic below the distress ratio jumped in 2015 and early 2016 as the oil price slumped. The ratio has fallen since then, with retailers, restaurants and telecommunication companies now the problem sectors.

The growth of covenant lite lending will substantially delay the transition of distressed companies into defaulted companies. With solid covenants, a default is triggered earlier giving the lenders an opportunity to ask for additional equity to right size the debt proportion of the capital stack. If the company can’t get more equity, bankruptcy happens fairly quickly, which typically enhances the recovery rate for senior lenders. Without covenants, the company continues to stagger along as a zombie until it can’t refinance an upcoming maturity or runs out of cash and facilities to drawdown. The Toy’s R US bankruptcy is an example of the zombie state persisting for years.

Watching the distress ratio will produce some false positives as was the case in late 2015 and early 2016. High yield debt sold off and there was a spate of oil and gas defaults, but the wider market held together well and recovered. I suspect the next downturn will be more like the financial crisis given how much further things have run since early 2016, but another false positive before a material downturn is also possible. Either way, the distress ratio will lead the default rate higher, with the next downturn likely to be a long, predictable horror movie full of zombies.

Anbang Bailout

The build up of speculative investments and dodgy debt in China has many postulating when it will face an inevitable reckoning. There’s been a series of investment groups collapsing where investors have lost their money. However, these have so far been smaller groups with limited recognition beyond their local areas. This all changed in April.

The Chinese insurance group/investment conglomerate Anbang received a US$9.7 billion bailout. Anbang had been on a global acquisition binge, with large slabs of debt used to fund the acquisitions. This included many debt products sold in China. The Chairman has admitted fraudulent activities and has seen his wealth and freedom evaporate.

There’s a couple of key points from this. First, the Chinese government has for now made a call that some groups are too big to fail. Taxpayers will bear the cost on this one. Second, the fact that a business this large failed so badly when the economy is still doing well is telling. Things will be so much worse when property prices, bond prices and stock prices correct. Third, moral hazard is building in China. Covering up one mess allows others to grow larger as investors are emboldened to take more risk.