The downgrade of Ford Motor Co this week by Moody’s from Baa3 to Ba1 (equivalent to BBB- and BB+ rating monikers for Standard and Poor’s) opens up the question of whether an investment grade rating still matters. (Click here for a primer on credit ratings.) The short answer is not as much as it used to.

With the continued chase for yield, driven by central banks in Europe and Japan setting overnight rates at negative levels, the gap in return between different credit risk bands has fallen below normal, historical levels. Wolf Richter recently highlighted that fourteen sub-investment grade rated European corporates had bonds trading at negative yields. That means you lose money holding those bonds, as well as risking losing a lot more if the company defaults!

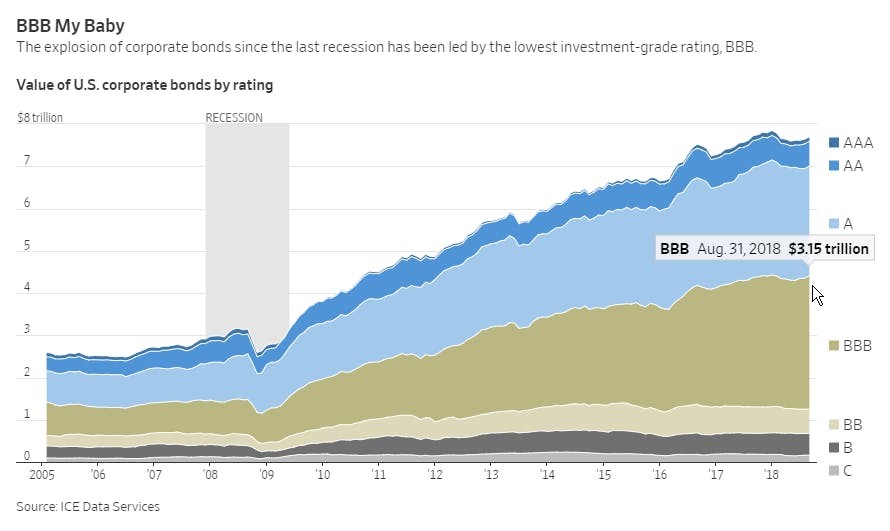

That drop in the yield differential has in turn led global companies to move away from more conservative credit risk profiles choosing instead to leverage up, typically to buy back stock or pay dividends. The graph below from Mike Shedlock’s website shows that American AAA’s and AA’s haven’t changed much, but A’s and BBB’s have exploded.

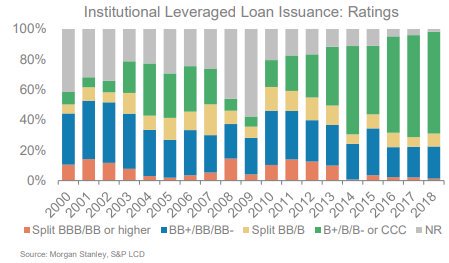

Similarly, lower sub-investment grade ratings have roared back since 2009, with the chart above understating that growth as it doesn’t include the rapid expansion of the leveraged loan market. The chart below of the split of leveraged loan ratings from Driehaus Capital shows the rating deterioration in leveraged loans.

For investors, the decline in both the interest rate or “risk free” component of return as well as the decline in credit spreads has led to a push down the credit risk spectrum. This is often under the guise of “multi-sector” or “go anywhere” credit mandates, where the portfolio manager is given the licence to pursue whatever securities and sectors they believe are best value at the time. If the investor has given the manager a return target, that will likely lead to the credit manager taking greater credit risks (lower ratings, more volatile sectors and covenant light debt), targeting more illiquid securities and more duration risk to continue to hit the return target.

For example, a manager working US corporate credit with a target of 2% above the risk free rate would have been able to get that from BBB bonds from 2008 through to mid-2016. Today, the average BBB spread is 1.53% and the average BB spread is 2.17%. If the manager had a target based on nominal yields and a longer view it gets worse. In the years before the financial crisis, US BBB bonds were offering a yield of around 6%. Today the B rated average yield is 5.75%.

The obvious temptation at this late point of the credit cycle is to chase yield and to accept lower credit ratings, weaker covenants and longer duration for just a little bit more yield. The explosive growth in private debt is another response, though the yield premium and lower risk previously available in most sectors has substantially fallen away in recent years. Australia remains something of a Treasure Island, with the pullback by banks opening up space for others to earn good returns in property lending, securitisation and some parts of the corporate lending sectors.