Australians have rightly applied the blowtorch to their politicians for housing being increasing unaffordable. The Federal Treasurer, Scott Morrison, has now turned the blowtorch onto financial regulators for their part in the problem. Whilst the majority of the problem is caused by the policy failures of politicians, regulators have ignored their contribution to the bubbly conditions and have sought to blame each other. APRA, ASIC and the Reserve Bank have all failed to take obvious and logical action which would have taken some of the heat out of housing markets.

The combination of low interest rates, weak lending standards and low capital requirements for high risk mortgages have encouraged Australia consumers to borrow heavily for housing. Australia now has one of the highest household debt ratios in the world with much of the bank funding for this debt binge coming from overseas. Australian consumers are stretched with record calls to the national debt counselling hotline at a time when unemployment and interest rates are both low. If either unemployment or interest rates rise materially, there will be a wave of defaults.

Financial regulators have responded by making speeches about a housing bubble but have taken little action. ASIC’s shadow shopping exercise in 2015 revealed loose lending standards, but the late 2016 study by UBS found that mortgage fraud was still systemic. APRA’s use of macroprudential tools has been miniscule compared to its equivalents in New Zealand and Singapore, who are also dealing with high property prices. The RBA has made the situation worse by cutting rates in 2015 and 2016, ignoring the surge in house prices and lending after its rate cuts.

Australian regulators have failed to learn the lessons of the subprime crisis in the US and have forgotten many of the lessons from the Australian property collapse and recession in the early 1990’s. There’s talk that the rocket from Scott Morrison has them contemplating action. The sections below outline what each should have started doing years ago to fulfil their respective roles in creating a stable financial system.

RBA

The RBA needs to expand its definition of financial stability and increase the cash rate. The RBA rightly focusses on consumer price inflation and wage inflation, but it has ignored debt growth and asset price growth. As lending increasingly moves into the Minsky categories of speculative and ponzi, the reserve rate must increase to discourage further growth in high risk debt.

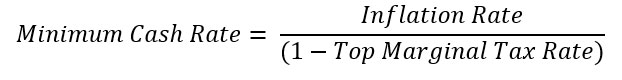

The RBA should also be mandated to end financial repression. Financial repression describes measures used by governments to hold down interest rates. This is effectively a tax on savers with the benefit transferred to borrowers. As the federal government is increasingly indebted after years of budget deficits it benefits from low interest rates. By setting the inflation target for the RBA too high, the federal government is implicitly taxing savers for its own benefit. To prevent financial repression the RBA should be required to ensure that the cash rate allows all citizens to receive a positive after-tax real rate of return. This can be expressed as:

An independent RBA should embrace this rule as it will stop the federal government from using financial repression to deal with budget deficits.

APRA

As Australian banks are dependent upon overseas funding for their ever expanding balance sheets, they cannot afford to have any questions about their solvency. In a time of crisis, banks will turn to the RBA’s liquidity facilities for funding and Australian taxpayers will be on the hook if a bailout is needed. The obvious way to mitigate this risk is to increase capital levels to unquestionably strong levels, as was recommended by the Murray inquiry. This means four actions should be taken immediately.

Firstly, the low levels of capital held against high risk residential mortgages must increase. The 25% minimum that APRA mandates should be subject to a 2.5% increase for every 1% the LVR increases beyond 70%. This implies a 70% LVR carries a 25% risk weight, an 80% LVR carries a 50% risk weight and a 90% LVR loan carries a 75% risk weight. This would see banks introduce risk based pricing for residential mortgages. High risk loans would be greatly reduced with borrowers given the carrot of lower interest rates if they save a larger deposit or lower their borrowing amount.

Secondly, total capital levels should be ramped up, which can be cheaply done by requiring banks to sell more hybrids and subordinated debt. Increasing capital to the high watermark Switzerland is heading towards is estimated to increase the cost of funds of Australian banks by 0.19%. This is a small price to pay for greatly reduced solvency risk.

Thirdly, the evidence of excessive debt and risk taking means the counter-cyclical capital buffer should be at or near the top of the 0-2.5% band. APRA’s decision to leave the buffer at 0% this year indicates that APRA sees no systemic risk at all from current high levels of household debt, credit growth and loose lending standards.

Fourthly, macro-prudential measures should be implemented include limiting banks to owner-occupied lending up to 90% LVR and investor lending to 75% LVR. APRA should also ban banks from making interest only loans where the LVR is above 75%. Loan terms should be capped at 25 years, with full amortisation required in that time. In the current environment with historically low interest rates and elevated property prices these four APRA initiated measures would substantially reduce speculative lending and reduce the risk of banks becoming insolvent.

ASIC

ASIC is accountable for seeing that responsible lending legislation is complied with. Contrary to the “buyer beware” approach adopted by some lenders, responsible lending legislation places the onus on lenders to ask for information, verify it and make an assessment that the loan is not unsuitable. The high occurrence of mortgage fraud, increasing financial stress and basic case studies show that this simply isn’t happening.

ASIC has begun a crackdown with Westpac the first to face court proceedings. ASIC has said another ten lenders are being investigated. What’s lacking for lenders is a clear list of actions that must be taken to be compliant such as:

- Insisting on completed income, expenses, assets and liability statements on the application form

- Collecting payslips or alternative verification (BAS statements, bank account statements) to confirm income

- Discounting rental income for vacancies, as well as costs of owning, tenanting and maintaining the property

- Enquiring about the likelihood of life events such as caring for children/parents, unemployment, sickness, maternity leave and retirement to ensure appropriate headroom in serviceability and the equity contribution

- Applying a 3% interest rate increase to the current interest rate (up from 2% following the RBA rate cuts in 2015 and 2016) to test serviceability

- Using the higher of stated expenses or Household Expenditure Measure, not the Henderson Poverty Index

- Limiting interest only periods to five years and the total loan period to 25 years

Conclusion

Like politicians, Australia’s financial regulators have made plenty of noise about housing being in a bubble but have taken little action. Their failure to respond within their respective mandates will be seen as negligence if Australia has a recession in the medium term. The 25 year gap since Australia’s last recession means many now ignore the increasing possibility of another recession. The high levels of household debt and the dependence upon an enormous federal deficit to stimulate the economy mean that Australia’s financial stability is built on unstable foundations. Continuing to delay action will only increase the hangover when this party ends.