It’s that time of year when financial commentators write their predictions for 2022, or for the more bearish their biggest risks for the year ahead. Bill Blain has put forward that out of many things to worry about in 2022, dumb politics and euphoric credit markets are the biggest risks. It’s hard to disagree when looking at how many governments have effectively adopted MMT. This isn’t partisan either, both left and right governments in most developed economies are happily running massive deficits with no plans to get back into surplus, or at least not until the current generation of politicians are likely to have moved on.

The risk of inflation staying above 5% in the US for an extended period is generally considered minimal. However, with the constant stream of evidence of higher wages and limited appetite to reign in deficits and digital money printing, inflation could be far sticker than expected. Take the time to read a quick summary of how inflation got out of control in the 1970’s and note the key factors. Central banks aggressively targeting full employment, large scale monetary and fiscal stimulus, a desire to avoid a recession at all costs and central banks dithering when inflation took off were all present then and now.

The risk of sustained higher inflation brings in the risk that a modern day Paul Volcker is needed to get inflation back under control. A period of normal to high interest rates would shock much of the debt markets, which are largely working on the assumption that higher interest rates aren’t possible. For government bonds, an overnight rate of 4% could easily see 10 year bonds knocked down by 20%. Long duration assets (equities, property and infrastructure) could be similarly hit if investors factored in a higher risk-free rate.

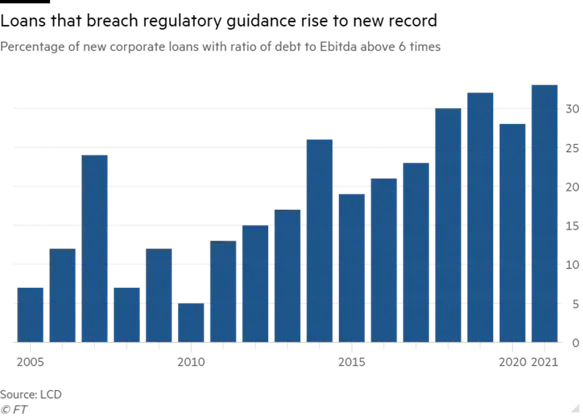

Sub-investment grade credit could be particularly badly impacted. As the graph below from the Financial Times shows, the proportion of high debt to EBITDA loans is much higher than it was in 2007. Covenant light loans are standard now when they were a minority in 2007.

High debt levels only work if economic growth is strong or if interest rates remain low. A Volcker like correction would cut a swathe through heavily indebted borrowers, with bankruptcies and debt to equity swaps required to right size debt levels. It is common to hear investors in leveraged loans saying there’s no need to worry as their floating rate debt will receive higher interest payments when central banks start to increase overnight rates. There’s an assumption that the borrowers can afford to pay the higher rates, if they can’t the lost principal could quickly overshadow the gains from higher rates. There are two conclusions from this analysis. First, there’s limited reward for taking additional risk in most sectors, so target overlooked and cheaper sectors and take risk there. Second, keep your interest rate duration short.