One of the big advantages of being a debt investor is that you can make long term investment decisions with far fewer short term consequences than an equity investor. There is no equivalent to Tesla or Afterpay in debt, stocks that all but guarantee underperformance if you’ve held less than the standard weighting in the last six months. With a debt portfolio the risk is the other way around, as buyers of the Virgin bonds have found out the hard way.

Given avoiding bad risks is the key to outperforming on debt investments, I focus much of my investment analysis and writing on identifying those bad risks. My calls to avoid bonds from Virgin Australia and Argentina have worked out well. Others I’ve written about are still bad risks but haven’t defaulted yet. As I’m not shorting these names there’s no cost to client portfolios in being early. With debt it helps to remember two truisms:

- If it’s unsustainable, it will eventually end, and

- Borrowers go broke slowly and then suddenly

The first is a rewording of Stein’s Law, coined by American economist Herbert Stein. The second is a summary of a discussion between two characters in an Ernest Hemingway book “The Sun Also Rises”. I’ve thought of these truisms recently when I saw the following two graphs.

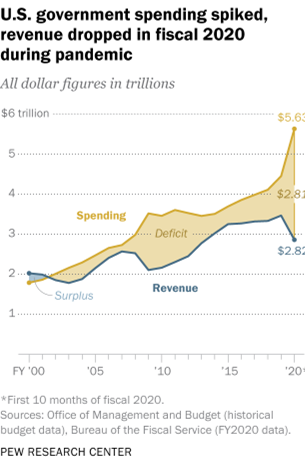

This first graph comes from a Pew Research Center article that notes whilst the US Federal budget deficit has blown out enormously, public concern with it has fallen. Perhaps the public is listening to short term focussed politicians and political appointees spouting mistruths like “now is not the time to worry about shrinking the deficit”.

The US Government is now collecting one dollar in revenue for every two dollars it spends. Obviously, this mismatch will reduce if the economy recovers in a reasonable fashion, but the enormous deficits under Obama that have increased under Trump are unsustainable. Not talking about the issue now is a convenient way to put off the inevitable, but it’s completely the wrong way around. As Peter Costello has often said “the easiest spending cut you’ll ever make is the new spending you never go into”. Australia’s ability to waste enormous sums of money during the global financial crisis and now in the pandemic crisis are due to his economic legacy built on budget surpluses.

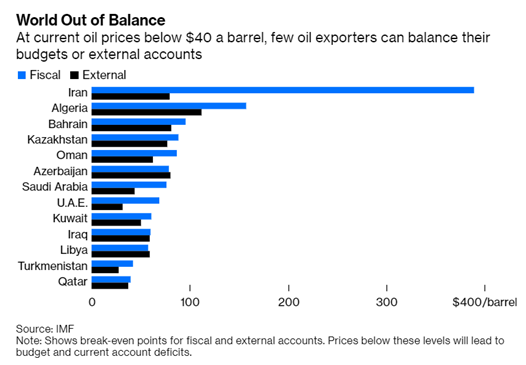

The second graph is taken from a Bloomberg article that highlights the likely woes ahead for nations heavily dependent on oil production. Note that many of these countries need oil prices near or above $100 a barrel to balance their budgets. If the last decade’s shale boom remains a good guide, whenever the oil price surpasses $50 a barrel, US producers greatly increase their production and put a quasi-ceiling on the oil price. There’s also the current economic downturn, which is reducing demand and will take several years to clear. Expecting an average long term price above $60 a barrel seems unsustainable, which makes massive budget cuts for most of the above countries inevitable.

When it comes to corporate debt, study after study concludes that the proportion of companies fitting the zombie definition is rising. Ultra-low interest rates and quantitative easing are providing cover, allowing many zombie businesses to postpone an inevitable restructuring. However, debt maturities particularly when lenders are focussed on their long term self-interests or when distressed debt funds have bought into the debt, will force the issues to be addressed over the next three years.

For household debt, government stimulus in many developed nations has more than offset lost employment income when measured on an aggregate basis. The expected reduction of government stimulus in 2021 means that over-indebted borrowers will need to deal with their financial problems. For some this will be through bankruptcy and others through the sale of highly leveraged investment properties.