When an economic crisis arrives, there’s often two key economic arguments that play out. First, how much government stimulus should occur to replace the reduced business and consumer spending? Second, does the quality of spending matter or is it simply a matter of getting the money circulating? The classic Keynesian response is to borrow to increase government spending and to worry more about the speed of the stimulus than the quality. The classic Austrian response is to cut government spending and taxation, with remaining government spending focussed on the basic services the private sector cannot do well. (e.g. military, police)

In some ways, both responses can be argued to be beneficial if a different time frame is used to judge them. Keynesian responses do provide short term stimulus but place an anchor on future economic growth. There is no free lunch, usually there is higher taxation and/or lower governments spending in the future as a result. Sometimes the cost isn’t paid via an explicit tax, but via an underhanded equivalent such as financial repression or higher inflation. Keynesian responses also increase moral hazard behaviours, increasing the frequency and severity of future economic busts.

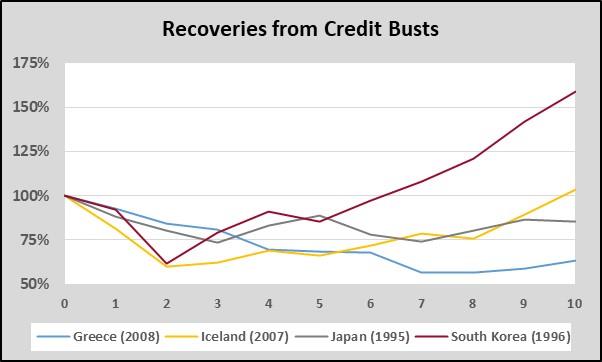

The Austrian response of cutting government spending and taxation will have a less positive short term impact compared to running a substantial budget deficit. However, it sets a country up for a faster and stronger long term recovery. South Korea (Asian Financial Crisis) and Iceland (Global Financial Crisis) are good examples of countries that had partied way too hard before a crisis and had to rapidly sober up. Whilst their economies shrank as the debt fuelled booms were unwound, the economic turnarounds meant that they were able to surpass their previous (debt inflated) peaks over time. Contrast this with Japan and Greece, which have failed to break out of long term funks.

One thing a crisis exposes is the quality of debt, particularly the economic value of the activities that were funded by debt. Here China is proving to be a particularly good illustration of what not to do. In recent decades China has used its growing economic might to lend to African nations. The projects often have a political angle, either by being a key piece of infrastructure that China can exploit or a grandiose project that ingratiates China with the local rulers.

The combination of China not being an experienced lender and the projects often having little or no ability to generate sufficient revenue to service the debt is now coming sharply into view. African nations are turning on China, demanding that it renegotiate loans on white elephant projects. In some cases, newly elected governments are looking to disclaim the debts of previous governments pointing to the corruption that occurred and the minimal benefit from the project.

Back in China, the bailouts of financial institutions continue. This week the Chinese government nationalised four insurers, three securities firms and two trust companies with a combined $143 billion in assets. This follows a string of regional bank failures last year, with rumours of many more to come as the Covid-19 economic contraction and trade disputes slash demand for China’s exports. Whilst it is difficult to know how far down the rabbit hole goes, estimates range from 10-30% of bank loans being non-performing. If even the low end of the range turns out to be accurate, it will be more than enough to require nationwide bailouts of banks of all sizes.